This essay by Peter Rushton was first published in January 2022 to celebrate the award of the Robert Faurisson International Prize to Monika Schaefer and Alfred Schaefer

It is dedicated to three great Europeans of our time:

Ursula Haverbeck, Lady Michèle Renouf and Isabel Peralta:

Defenders of the right to historical truth –

Champions of European civilisation’s essential values.

After fifty-four months of titanic struggle, waged on both sides with unexampled fury,

the German people now finds itself alone, facing a coalition sworn to destroy it.

War is raging everywhere along our frontiers. It is coming closer and ever closer.

Our enemies are gathering all their forces for the final assault. Their object is not

merely to defeat us in battle but to crush and annihilate us. Their object is to

destroy our Reich, to sweep our Weltanschauung from the face of the earth, to

enslave the German people – as a punishment for their loyalty to National

Socialism. We have reached the final quarter of an hour.

The situation is serious, very serious. It seems even to be desperate. We might

easily give way to fatigue, to exhaustion, we might allow ourselves to become

discouraged to an extent that blinds us to the weaknesses of our enemies. But these

weaknesses are there, for all that. We have facing us an incongruous coalition,

drawn together by hatred and jealousy and cemented by the panic with which the

National Socialist doctrine fills this Jew-ridden motley. Face to face with this

amorphous monster, our one chance is to depend on ourselves and ourselves alone; to

oppose this heterogenous rabble with a national, homogenous entity, animated by a

courage which no adversity will be able to shake. A people which resists as the

German people is now resisting can never be consumed in a witches’ cauldron of

this kind. On the contrary; it will emerge from the crucible with its soul more

steadfast, more intrepid than ever. Whatever reverses we may suffer in the days that

lie ahead of us, the German people will draw fresh strength from them; and

whatever may happen today, it will live to know a glorious tomorrow.

The will to exterminate which goads these dogs in the pursuit of their quarry gives us no

option; it indicates the path which we must follow – the only path that remains open to

us. We must continue the struggle with the fury of desperation and without a glance

over our shoulders; with our faces always to the enemy, we must defend step by step the

soil of our fatherland. While we keep fighting, there is always hope, and that, surely,

should be enough to forbid us to think that all is already lost. No game is lost until the

final whistle. And if, in spite of everything, the Fates have decreed that we should once

more in the course of our history be crushed by forces superior to our own, then let us go

down with our heads high and secure in the knowledge that the honour of the German

people remains without blemish. A desperate fight remains for all time a shining

example. Let us remember Leonidas and his three hundred Spartans! In any case, we

are not of the stuff that goes tamely to the slaughter like sheep. They may well

exterminate us. But they will never lead us to the slaughter house!

No! There is no such thing as a desperate situation! Think how many examples of

a turn of fortune the history of the German people affords! During the Seven Years’

War, Frederick found himself reduced to desperate straits. During the winter of

1762 he had decided that if no change occurred by a certain date fixed by himself, he

would end his life by taking poison. Then, a few days before the date he had chosen,

behold, the Tsarina died unexpectedly, and the whole situation was miraculously

reversed. Like the great Frederick, we, too, are combating a coalition, and a coalition,

remember, is not a stable entity. It exists only by the will of a handful of men. If

Churchill were suddenly to disappear, everything could change in a flash! The British

aristocracy might perhaps become conscious of the abyss opening before them – and

might well experience a serious shock! These British, for whom, indirectly, we have

been fighting and who would enjoy the fruits of our victory….

We can still snatch victory in the final sprint! May we be granted the time to do so!

All we must do is to refuse to go down. For the German people, the simple fact of

continued independent life would be a victory. And that alone would be sufficient

justification for this war, which would not have been in vain. It was in any case

unavoidable; the enemies of German National Socialism forced it upon me as long

ago as January 1933.

Adolf Hitler, 6th February 1945

An extensive interview with the late Professor Robert Faurisson entitled ‘The Gas Chambers: Truth or Lie?’ appeared in August 1979’s edition of the popular Italian magazine Storia Illustrata (‘History Illustrated’), owned by the leading publishing house Mondadori. It now appears for the first time in proper English translation.

The questions and answers address numerous aspects of ‘the Holocaust’ in a detailed and serious manner, a venture sadly impossible on the part of any mainstream journal in 2022: free discussion of this topic is proscribed on pain of long imprisonment in many countries, and effectively forbidden by academic and media self-censorship in almost all others.

This essay written to accompany the newly published piece from those bygone freer times will focus on one particular detail, where Faurisson quotes from a still-controversial document – The Testament of Adolf Hitler – that purports to record comments made by Hitler across several dates in February 1945 and on 2nd April 1945. (In a footnote added in 1997, Faurisson partly retracts these quotations, since he had come to regard the document in question as probably inauthentic.)

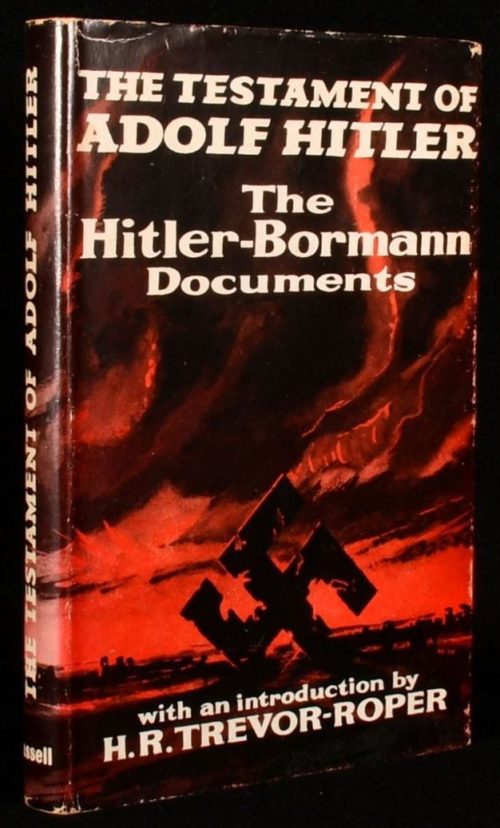

Published first in French translation as Le Testament politique de Hitler in 1959, in English excerpts that year for Daily Express serialisation, then two years later as a book in English – The Testament of Adolf Hitler: The Hitler-Bormann Documents, February-April 1945, this controversial text was not issued in a German edition until 1981 – Hitlers politisches Testament, usually known in German by its subtitle the Bormann-Diktate (“Bormann Dictations”). I shall refer to it in this essay as The Testament, but it should not be confused with Hitler’s “last will and testament”, which he dictated to his secretary Traudl Junge and signed at 4 am on 29th April 1945 in the Berlin bunker.

In format and provenance, The Testament could be regarded as a ‘sequel’ to the far better known Hitler’s Table Talk (first published in German as Tischgespräche im Führerhauptquartier), a record of comments made by the Führer to his inner circle, beginning in the summer of 1941 and ending in late 1944.

The Testament is quoted by Faurisson when answering his interviewer’s question on pp. 10-11 (as originally printed) of ‘The Gas Chambers: Truth or Lie?’ The Professor states: “Never did Hitler order or allow that anyone should be killed on account of his race or religion.” In the same paragraph he acknowledges that “Hitler was anti-Jewish and racist”, but suggests that he was “against colonialism” – and it is on this latter point that he quotes from The Testament, recording that on 7th February 1945 Hitler said to his close collaborators:1While not specified in the interview, these words about colonialism are from François Genoud (ed.), The Testament of Adolf Hitler: The Hitler-Bormann Documents, February-April 1945, tr. R.H. Stevens (Cassell, 1959), p. 44.

“The white races did, of course, give some things to the natives, and they were the worst gifts that they could possibly have made, those plagues of our own modern world – materialism, fanaticism, alcoholism and syphilis. For the rest, since these peoples possessed qualities of their own which were superior to anything we could offer them, they have remained essentially unchanged. […] One solitary success must be conceded to the colonisers: everywhere they have succeeded in arousing hatred.”

In 1997 Faurisson added a correction to his copy of the 1979 interview: “on reflection, this book seems to me to be a forgery for which François Genoud, recently deceased, may be responsible. British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper states in his long preface that the text is indubitably authentic. In my opinion he is mistaken.” (Hugh Trevor-Roper, later Lord Dacre (1914-2003), was one of the most eminent British historians of the 20th century. From 1957 to 1980 he was Regius Professor of Modern History at Oxford, one of the most prestigious academic posts in the world.)

By happy coincidence, today’s English translation of the interview (including its 1997 amendments) comes at a time when it is possible to re-examine the contents and authenticity of The Testament and the respective roles of the Swiss banker François Genoud and Trevor-Roper. The Swedish scholar Dr Mikael Nilsson has devoted several years to a detailed study of both Hitler’s Table Talk and The Testament. He is very critical of Genoud and Trevor-Roper and concludes that neither text is reliable. After several articles on the topic in academic journals, Nilsson has now published a 400-page book2Mikael Nilsson, Hitler Redux: The Incredible Story of Hitler’s So-Called Table Talks (Routledge, 2021). denouncing the purported Hitler transcripts: Hitler Redux: The Incredible Story of Hitler’s So-Called Table Talks.

However, Nilsson did not have the benefit of studying a British document on this matter3PREM 11/3062. Unless indicated otherwise, all catalogue references in these footnotes refer to documents consulted by the author at the UK National Archives.: a document that remained secret for more than sixty years and was only released to the UK National Archives in January 2021 after he had already completed his book. It is not available online, but I have visited the National Archives at Kew to examine this document and other relevant material.

The present essay is therefore the first attempt – in the light of this new archival discovery – to assess the authenticity of The Testament and the conduct of Trevor-Roper. Even if we are unable to reach a definitive conclusion on the former point, the attempt to do so will take us on a historiographical journey that sheds light on numerous topics of interest for revisionists and for any honest scholar of the Third Reich’s legacy to our times.

We should first look at the timing of Faurisson’s decision in 1997 to correct his earlier statement and express strong doubts about The Testament. We should bear in mind that during the mid-1990s the revisionist community had been riven by a bitter and costly dispute within what was then by far the most influential and best-funded revisionist organisation – the Institute for Historical Review (IHR). Though Faurisson was not personally involved in the lawsuits, he found himself aligned with the IHR faction opposed to its co-founder Willis Carto.

This is relevant to the present matter because in becoming critical of Carto, the Professor’s critical attention could hardly avoid being drawn to the aforementioned Genoud. Central to the dispute between Carto and his former associate Mark Weber (who eventually won control of the IHR) was the question of a legacy from Mrs Jean Farrel, an American widow who latterly lived in Switzerland. It was revealed in court4Legion for the Survival of Freedom, Inc. vs Willis Carto et al., Superior Court of the State of 4

California in and for the County of San Diego, transcript, 8th November 1996. that as part of the complex process of securing the Farrel legacy, Willis Carto had paid $800,000 to Genoud, a man with high-level contacts dating back more than fifty years among veteran National Socialists. (Genoud died aged 80 in May 1996.)

Having had little reason previously to look closely at Genoud or the extent to which his past record might lead one to look askance at The Testament, Prof. Faurisson now had special reasons for doing so – being a man devoted to intellectual consistency, he could not doubt Genoud’s honesty in one field without at least questioning it in another. Moreover, on the one occasion when he could discuss the matter face to face with Genoud, Faurisson had been concerned5Private information. to discover that the latter did not have access to the original German documents on which The Testament was based.

Though he never had the opportunity to carry out detailed research on the topic, Faurisson is far from alone in doubting The Testament’s authenticity. Among the sceptics (though most historians still regard the text as genuine) are two very different Englishmen who are also two of the world’s leading experts on Hitler – David Irving and Sir Ian Kershaw. Irving states on his website6www.fpp.co.uk/Hitler/docs/Testament/GenoudMS.html that in 1979 Genoud gave him a copy of The Testament’s typescript and later admitted to him that he had in effect made the whole thing up, with the excuse: “But it is just what Hitler would have said, isn’t it?”

(There had been some controversy during 19927Brian Cathcart, ‘Who has the right to publish the diaries’, Independent on Sunday, 5th July 1992; and Rosie Waterhouse et al., ‘Irving back to anti-Nazi fury’, Independent on Sunday, 12th July 1992. over rights to the Joseph Goebbels diaries: Genoud claimed he owned the copyright, but after a complete text of the diaries was discovered in a Moscow archive, the Sunday Times went ahead and published extracts – paying Irving a fee for his essential assistance but nothing to Genoud. Even in 2015, almost twenty years after his death, copyright disputes linked to Genoud involving National Socialist diaries and other documents continued to trouble the courts.8Roger Kimball, ‘Suing to Profit from a Nazi’s Diaries’, Wall Street Journal, 16th July 2015.)

Meanwhile and less definitely, Irving’s fellow historian Kershaw wrote9Ian Kershaw, Hitler 1936-1945: Nemesis, pp. 1024-1025 (Allen Lane, 2000). (while curiously misstating the date of The Testament’s discovery and publication), taking a cautionary if not sceptical line:

“The tone of the monologues is unmistakably that of Hitler. The themes are familiar, as are the rambling style and the discursive dips into history. There is talk, among other topics: of Churchill’s responsibility (influenced by Jews) for the war; of Britain’s rejection of German peace-offers which would have enabled the destruction of Bolshevism and saved the British Empire; of an unnatural coalition aiming to destroy Germany, a will to exterminate which gave the German people no other choice but to continue the struggle; of the example of Frederick the Great; of the need for eastward expansion, not the quest for colonies; of exposing to the world ‘the Jewish peril’ and of his warning to Jews on the eve of the war; of the timing and necessity of the war against the Soviet Union; of the difficulties caused for Germany by Italy’s weakness and blunders; of regrets that Japan did not enter the war against Russia in 1941, and the inevitability that the United States would enter the war against Germany; of the missed chance of going to war in 1938, which would have given Germany an advantage; of time always being against Germany; of being compelled to wage war as Europe’s last hope; and of the need to uphold the racial laws, and claim on gratitude for having eliminated Jews from Germany and central Europe. [Yet note below that in fact The Testament does not speak of physically eliminating Jews.] The monologues have a self-justificatory ring to them. They are intended for posterity, establishing a place in history. They have a reflective readiness – unusual, if not unique, for Hitler – to contemplate responsibility for errors, for example, in policy towards Italy and Spain.

“The monologues were not, as those from 1941–4 were, the product of musings during meals attended by others in his entourage, or during the ‘tea hours’ with his secretaries. Neither a secretary nor anyone else mentioned them at the time, or apparently knew they were being compiled. Gerda Christian (formerly Daranowski), writing to Christa Schroeder long after the war,10The former Gerda Daranowski wrote to Christa Schroeder on 19th March 1975, and is quoted in Christa Schroeder, He Was My Chief: The Memoirs of Adolf Hitler’s Secretary (English edition, Pen & Sword, 2009). Her comments seem directed at the Table Talk (more particularly the claims of its editor Henry Picker that Hitler had given him exclusive rights to write up these comments). Gerda Daranowski / Christian wrote: “You know how he (Hitler) hated having his thoughts committed to paper, i.e. he strictly forbade it. I remember one night at Wolfsschanze when after some highly interesting talk you said to him something like: ‘I would like to have got that down in shorthand’ and he replied: ‘No, then I would not be able to speak so freely’ etc. etc., do you remember?” did not regard them as authentic, though she accepted that they could be a compilation of Hitler’s thoughts in the last months. She ruled out a possibility of Hitler summoning Bormann to dictate to him, pointing out from her own recollection how he hated verbatim accounts on paper of what he had said casually. The main problem with the authenticity of the text is that no reliable and certifiable German version exists. It is impossible, therefore, to be certain. A great deal has to be taken on trust; and even then no safe mechanism for checking is available.”

From the standpoint of a believer in orthodox Holocaustianity, it is easy to see why the contents of The Testament are problematic: if one’s a priori assumption is that Adolf Hitler ordered the systematic murder of six million Jews in homicidal gas chambers, then one might expect to find – if not specific references to this mass killing – at least some firm evidence pointing to the fact of these mass killings and/or homicidal mania in general. All the more so when there is an entire section of The Testament devoted to the Jewish Question.

Some mainstream exterminationists have quoted or paraphrased The Testament to imply (falsely) that it does contain such evidence. For example the Dutch historian Annemarike Stremmelaar (from Leiden University’s Centre for the Study of Islam) has written11Annemarike Stremmelaar, ‘Reading Anne Frank: Confronting Antisemitism in Turkish Communities’, in Evelien Gans and Remco Ensel (eds.), The Holocaust, Israel and ‘the Jew’: Histories of Antisemitism in Postwar Dutch Society (Amsterdam University Press, 2016), pp. 472-473. about a 2013 Dutch television programme that became famous for ‘exposing’ the scale of ‘antisemitism’ among Turkish pupils in Dutch schools. In a filmed interview one boy says: “What Hitler said about the Jews is that there will be one day when you will prove me right that I killed all the Jews. Yes, that day will come.”

Dr Stremmelaar writes that no-one has yet been able to trace the origin of this boy’s statement, “so far it has been impossible to trace it back to either Islamist or neo-Nazi media”, but she notes:

“One commentator wrote that Hitler’s alleged quote ‘one day you will prove me right that I killed all the Jews’ is frequently used in Islamist propaganda. While conceding that it is unknown where the boy read the quote, the commentator assumes it is quite likely he read it in Islamist propaganda rather than in neo-Nazi literature. The original source may be the so-called Bormann-Diktate, which Hitler supposedly dictated to his secretary Bormann in the final weeks of his life.”

Is there any such statement attributed to Hitler in The Testament?

Chapter 5 of The Testament purports to record the Führer’s comments about Jewry12François Genoud (ed.), The Testament of Adolf Hitler: The Hitler-Bormann Documents, February-April 1945, tr. R.H. Stevens (Cassell, 1959), pp. 50ff. on 13th February 1945, beginning as follows:

“It is one of the achievements of National Socialism that it was the first to face the Jewish problem in a realistic manner.

“The Jews themselves have always aroused anti-semitism. Throughout the centuries, all the peoples of the world, from the ancient Egyptians to ourselves, have reacted in exactly the same way. The time comes when they become tired of being exploited by the disgusting Jew. They give a heave and shake themselves, like an animal trying to rid itself of its vermin. They react brutally and finally they revolt.”

One can see that exterminationists might assume that having defined the Jew as a parasite, Hitler is implying that Jews had to be wiped out, but The Testament’s next paragraphs should be read carefully:

“National Socialism has tackled the Jewish problem by action and not by words. It has risen in opposition to the Jewish determination to dominate the world; it has attacked them everywhere and in every sphere of activity; it has flung them out of the positions they have usurped; it has pursued them in every direction, determined to purge the German world of the Jewish poison. For us, this has been an essential process of disinfection, which we have prosecuted to its ultimate limit and without which we should ourselves have been asphyxiated and destroyed.

“With the success of the operation in Germany, there was a good chance of extending it further afield. This was, in fact, inevitable, for good health normally triumphs over disease. Quick to realize the danger, the Jews decided to stake their all in the life and death struggle which they launched against us. National Socialism had to be destroyed, whatever the cost and even if the whole world were destroyed in the process. Never before has there been a war so typically and at the same time so exclusively Jewish.

“I have at least compelled them to discard their masks. And even if our endeavours should end in failure, it will only be a temporary failure. For I have opened the eyes of the whole world to the Jewish peril.”

These are not the words of someone who has systematically murdered six million Jews – rather what he has set out to destroy is Jewish power (cultural, political and economic) in Germany. The war of physical destruction referred to in The Testament has been waged by Jewry against Germany.

This angle is pursued further in the following paragraph:

“One of the consequences of our attitude has been to cause the Jew to become aggressive. As a matter of fact, he is less dangerous in that frame of mind than when he is sly and cunning. The Jew who openly avows his race is a hundred times preferable to the shameful type which claims to differ from you only in the matter of religion. If I win this war, I shall put an end to Jewish world power and I shall deal the Jews a mortal blow from which they will not recover. But if I lose the war, that does not by any means mean that their triumph is assured, for then they themselves will lose their heads. They will become so arrogant that they will evoke a violent reaction against them. They will, of course, continue to run with the hare and hunt with the hounds, to claim the privileges of citizenship in every country and, without sacrificing their pride, continue to remain, above all, members of the Chosen Race. The shifty, the shamefaced Jew will disappear and will be replaced by a Jew vainglorious and bombastic; and the latter will stink just as objectionably as the former – and perhaps even more so. There is, then, no danger in the circumstances that anti-semitism will disappear, for it is the Jews themselves who add fuel to its flames and see that it is kept well stoked. Before the opposition to it can disappear, the malady itself must disappear. And from that point of view, you can rely on the Jews: as long as they survive, anti-semitism will never fade.”

Hitler later in the same monologue digressed on the topic of German racial pride,13ibid., pp. 53-55. before returning to the Jewish question:

“…When pride of race manifests itself in a German, as it sometimes does and in a most aggressive form, it is in reality nothing more than a compensatory reaction for that inferiority complex from which so many Germans suffer.”

Hitler indicated that in their own ways both the Prussians and the Austrians were different from other Germans in having developed a very particular sense of racial/cultural pride, before describing what he saw as his movement’s central mission:

“In its crucible National Socialism will melt and fuse all those qualities which are characteristic of the German soul; and from it will emerge the modern German – industrious, conscientious, sure of himself yet simple withal, proud not of himself or what he is, but of his membership of a great entity which will evoke the admiration of other peoples. This feeling of corporate superiority does not in any way imply the slightest desire to crush and overwhelm others. We have, I know, on occasions exaggerated our cult of this sentiment, but that was necessary at the outset and we were compelled to jostle the Germans pretty roughly in order to set their feet on the right road. In the nature of things, too violent a thrust in any direction invariably produces an equally violent thrust in the opposite direction. All this, of course, cannot be accomplished in a day. It requires the slow-moving pressure of time. Frederick the Great is the real creator of the Prussian type. In actual fact, two or three generations elapsed before the type crystallised and before the Prussian type became a characteristic common to every Prussian.”

Turning back to the original subject Hitler continued:14ibid., pp. 55-57.

“Our racial pride is not aggressive except in so far as the Jewish race is concerned. We use the term Jewish race as a matter of convenience, for in reality and from the genetic point of view there is no such thing as the Jewish race. There does, however, exist a community, to which, in fact, the term can be applied and the existence of which is admitted by the Jews themselves. It is the spiritually homogenous group, to membership of which all Jews throughout the world deliberately adhere, regardless of their whereabouts and of their country of domicile; and it is this group of human beings to which we give the title Jewish race. It is not, mark you, a religious entity, although the Hebrew religion serves them as a pretext to present themselves as such; nor indeed is it even a collection of groups, united by the bonds of a common religion.

“The Jewish race is first and foremost an abstract race of the mind. It has its origins, admittedly, in the Hebrew religion, and that religion, too, has had a certain influence in moulding its general characteristics; for all that, however, it is in no sense of the word a purely religious entity, for it accepts on equal terms both the most determined atheists and the most sincere, practising believers. To all this must be added the bond that has been forged by centuries of persecution – though the Jews conveniently forget that it is they themselves who provoked these persecutions. Nor does Jewry possess the anthropological characteristics which would stamp them as a homogeneous race. It cannot, however, be denied that every Jew in the world has some drops of purely Jewish blood in him. Were this not so, it would be impossible to explain the presence of certain physical characteristics which are permanently common to all Jews from the ghetto of Warsaw to the bazaars of Morocco – the offensive nose, the cruel vicious nostrils and so on.

“A race of the mind is something more solid, more durable than just a race, pure and simple. Transplant a German to the United States and you turn him into an American. But the Jew remains a Jew wherever he goes, a creature which no environment can assimilate. It is the characteristic mental make-up of his race which renders him impervious to the processes of assimilation. And there in a nutshell is the proof of the superiority of the mind over the flesh!…

“The quite amazing ascendancy which they achieved during the course of the nineteenth century gave the Jews a sense of their own power and caused them to drop the mask; and it is just that that has given us the chance to oppose them as Jews, self-proclaimed and proud of the fact. And when you remember how credulous the Germans are, you will realize that we must be most grateful for this sudden excess of frankness on the part of our most mortal enemies.

“I have always been absolutely fair in my dealings with the Jews. On the eve of war, I gave them one final warning. I told them that, if they precipitated another war, they would not be spared and that I would exterminate the vermin throughout Europe, and this time once and for all. To this warning they retorted with a declaration of war and affirmed that wherever in the world there was a Jew, there, too, was an implacable enemy of National Socialist Germany.

“Well, we have lanced the Jewish abscess; and the world of the future will be eternally grateful to us.”

In the German edition the sentence “I have always been absolutely fair in my dealings with the Jews” is rendered differently, with a metaphor which (as Nilsson points out) was also employed by Hitler in a different context in Mein Kampf. The German text has Hitler saying: Ich habe die Juden mit offenem Visier gekämpft (“I have fought the Jews with an open visor”).

One can see how the latter two paragraphs could (to a committed exterminationist or even just to a casual reader) be seen as amounting to an admission by Adolf Hitler that his Third Reich had set out to exterminate Jewry in a literal, physical sense – i.e. by the mass murder of Jews qua Jews.

Yet bear in mind that he is speaking in February 1945 when Germany’s defeat was all but certain. By this time all of the alleged ‘death camps’ – including the main alleged ‘killing factory’ of Auschwitz-Birkenau – were already in Soviet hands. Quite clearly, barring a miracle (which given the course of geopolitical affairs and the already incipient Cold War was by no means impossible) Germany had not exterminated Jewry, rather Jewry and its allies were about to wipe Germany off the map. The territory of Hitler’s Reich (indeed the territory of traditional pre-Hitler Germany) was soon to be divided among six states: the Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia, France, East Germany and West Germany.

So Hitler’s words here cannot amount to a proud admission that he had warned the Jews of their impending extermination and had proceeded to carry it out.

What his purported words in The Testament do mean to any careful reader is that National Socialism had identified a Jewish problem and had brought it to the surface. In response Jews had ceased being circumspect about their power and had openly proclaimed it, had blatantly declared their international war on Germany. And in response to this aggression, Hitler had warned them that they risked disaster for themselves.

A passing reference15ibid., p. 77. on 18th February 1945 underlines this point:

“It was only in 191516Although the USA did not declare war on Germany until 1917, Hitler is evidently referring here to President Woodrow Wilson’s intervention in February 1915 effectively taking the British side in insisting that the German Navy could not interfere with neutral shipping; and the subsequent German sinking of the Lusitania, a civilian liner secretly carrying British war munitions. that World Jewry decided to place the whole of its resources at the disposal of the Allies. But in our case, Jewry decided as early as 1933, at the very birth of the Third Reich, tacitly to declare war on us.17Note Hitler’s word ‘tacitly’: while recognising that the policy of World Jewry’s leaders was settled as early as 1933, he does not place undue weight on the now-notorious Daily Express headline of 24th March 1933 ‘Judaea declares war on Germany’. Furthermore the influence wielded by the Jews in the United States has consistently and steadily increased during the last quarter of a century. And since the entry of the United States into the war was quite inevitable, it was a slice of great good fortune for us to have at our side an ally of such great worth as Japan.”

Hitler was not deluded: he knew that Germany was (almost certainly) about to lose the war. But he could still claim to have “lanced the Jewish abscess” in the sense that the underlying poison had been released for all the world to see, and in this sense the future world would be grateful.

Right or wrong, and whether the text is genuine or a forgery, this is The Testament’s evaluation of the war between National-Socialism and World Jewry – and it is an evaluation that fails to bolster the orthodox ‘Holocaust’ narrative, indeed arguably contradicts it.

Neither is there any support for the Holocaustian narrative in a passage dated 24th February 1945,18ibid., pp. 87ff. where Hitler discusses international Jewry in the context of the USA:

“The war against America is a tragedy. It is illogical and devoid of any foundation of reality.

“It is one of those queer twists of history that just as I was assuming power in Germany, Roosevelt, the elect of the Jews, was taking command in the United States. Without the Jews and without this lackey of theirs, things could have been quite different. For from every point of view Germany and the United States should have been able, if not to understand each other and sympathize with each other, then at least to support each other without undue strain on either of them. Germany, remember, has made a massive contribution to the peopling of America. It is we Germans who have made by far the greatest contribution of Nordic blood to the United States.”

Note that here Hitler implicitly contradicts other statements that he makes in The Testament, to the effect that once a German transplanted himself to the USA he ceased to be a German and in fact became the enemy of his native land. Far from being evidence against the authenticity of The Testament, it seems to me that such contradictions help validate the text as at least a reasonably accurate record of the Führer’s spontaneous remarks as he turned over in his mind Germany’s increasingly desperate situation.

He continues:

“Unfortunately, the whole business is ruined by the fact that world Jewry has chosen just that country in which to set up its most powerful bastion. That, and that alone, has altered the relations between us and has poisoned everything.

“I am prepared to wager that well within twenty-five years the Americans themselves will have realized what a handicap has been imposed upon them by this parasitic Jewry, clamped fast to their flesh and nourishing itself on their life-blood. It is this Jewry that is dragging them into adventures which, when all is said and done, are no concern of theirs and in which the interests at stake are of no importance to them. What possible reason can the non-Jewish Americans have for sharing the hatreds of the Jews and following meekly in their footsteps? One thing is quite certain – within a quarter of a century the Americans will either have become violently anti-semitic or they will be devoured by Jewry.

“If we should lose this war, it will mean that we have been defeated by the Jews. Their victory will then be complete. But let me hasten to add that it will only be very temporary. It will certainly not be Europe which takes up the struggle against them, but it certainly will be the United States. …For the Americans, everything has so far been ridiculously easy. But experience and difficulties will perhaps cause them to mature.”

Hitler concluded that the naïve new American nation had been “an easy prey for the Jews” and that US involvement in the war had been against its interests:

“…to have flung them into the middle of a dog fight, as this criminal, Roosevelt, has done, was sheer lunacy. He, of course, has quite cynically taken advantage of their ignorance, their naïveté and their credulity. He has made them see the world through the eye of Jewry, and he has set them on a path which will lead them to utter disaster, if they do not pull themselves together in time.”

Nilsson partly acknowledges19Nilsson, Hitler Redux, p. 311. that “these passages are not really any more of an admission of genocide than some of the statements recorded in the Table Talks. After all, Hitler is not speaking about gassing millions of Jews to death in Auschwitz, Treblinka, and other camps or shooting thousands of Jews to death; these passages could just as well be interpreted as metaphoric, cultural, political, or spiritual extermination.”

Elsewhere Nilsson regards some of The Testament’s comments about Jews as evidence that the text is inauthentic. While there is no denying the depth and sincerity of Nilsson’s scholarship, there are numerous points where he is led into an over-dogmatic interpretation. Inadvertently, with his righteous ‘anti-nazi’ certainty he sometimes reveals the weakness of the exterminationist position.

As noted above, in the alleged 13th February text Hitler refers to the Jews as “first and foremost an abstract race of the mind” or a “spiritually homogeneous group” (rendered in the German version as “Gemeinschaft des Geistes”), and states that “in reality and from the genetic point of view there is no such thing as the Jewish race”. Nilsson however insists that “this goes against everything we know about Hitler’s views on the topic from all other sources”. In Mein Kampf, for example, Hitler had put the opposite case – that the Jews were a race and did not have the necessary idealistic character to become a spiritual community – and Nilsson quotes evidence that he had repeated this view as late as 1942.

For Nilsson this amounts to conclusive proof that “this statement [in The Testament] cannot have been made by Hitler.”

Yet this appears to be another assumption by Nilsson that the Führer was a fanatic with a fixed ideology (especially as concerned Jews) – an assumption commonly found among the ‘intentionalist’ school of ‘Holocaust’ historians who maintain that a policy of mass homicide towards European Jewry can be traced from Mein Kampf all the way to 1945’s Götterdämmerung. Nilsson goes on to speculate that refusing to define the Jews as a race would (from a National Socialist standpoint) help to undermine the case for a Zionist State. Therefore, he argues:20ibid., p. 328.

“The particular distortion of Hitler’s view of the Jews actually fit [sic] perfectly into Genoud’s political agenda to further Arabic nationalism, which has been well described in the biographies about him, since it could serve as a cogent argument against a Jewish nation-state: Israel.”

Actually one could use Nilsson’s own argument against him here, since we know that (partly for reasons of realpolitik) policy towards Zionism changed several times during the Third Reich. It is true that at one stage National Socialist policy was to encourage Jewish emigration to Palestine (and by extension to encourage Zionist organisations within Germany). Yet at other times the Zionist idea was explicitly denounced.

For example in Mein Kampf, Hitler famously wrote:21Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, tr. Ralph Manheim, (Pimlico, 1992), p. 294.

“While the Zionists try to make the rest of the world believe that the national consciousness of the Jew finds its satisfaction in the creation of a Palestinian state, the Jews again slyly dupe the dumb Goyim. It doesn’t even enter their heads to build up a Jewish state in Palestine for the purpose of living there; all they want is a central organisation for their international world swindle, endowed with its own sovereign rights and removed from the intervention of other states: a haven for convicted scoundrels and a university for budding crooks. It is a sign of their rising confidence and sense of security that at a time when one section is still playing the German, Frenchman, or Englishman, the other with open effrontery comes out as the Jewish race.”

Nevertheless, in a Munich speech on 6th July 1920 Hitler stated22Francis Nicosia, ‘Zionism in National Socialist Jewish Policy in Germany, 1933-39’, Journal of Modern History, Vol. 50 No. 4, on demand supplement (December 1978), p. D1259. that the Jews belonged in Palestine, and only there could they expect full rights as citizens; and Julius Streicher in an address to the Bavarian Landtag on 20th April 192623ibid. argued that German Jews should emigrate to Palestine. Moreover during the first four to five years of the Third Reich, Foreign Minister Konstantin von Neurath and successive heads of the Eastern Department at the Foreign Office (Hans Schmidt-Rolke, Hans Pilger, and Otto von Hentig) all pursued some form of pro-Zionist policy,24Francis Nicosia, The Third Reich & the Palestine Question (University of Texas Press, 1985), p. 51. typified by the so-called ‘transfer agreement’ that was strongly promoted by Germany’s Consul-General in Jerusalem from 1932-35, Heinrich Wolff. (Note that Wolff was not dismissed from active diplomatic service until September 1935,25ibid., p. 39. For discussion of the ‘transfer agreement’, see ibid., pp. 29ff.; also Edwin Black, The Transfer Agreement (Dialog Press, 1984); and Yehuda Bauer, Jews for sale? Nazi-Jewish Negotiations, 1933-1945 (Yale University Press, 1996). despite his wife’s being Jewish.)

Support for Zionism during those early years of the Reich was not restricted to the Foreign Office, for example the director of the Interior Ministry’s Jewish Department, Dr Bernhard Lösener, was also strongly pro-Zionist, writing in November 1935:26Nicosia, The Third Reich & the Palestine Question, p. 53.

“If the Jews already had their own state in which the greater part of their people were settled, then the Jewish question could be considered completely resolved today, also for the Jews themselves. The least amount of opposition to the underlying ideas of the Nürnberg Laws has been raised by Zionists, because they know at once that these laws represent the only correct solution for the Jewish people as well. For each nation must have its own state as the outward form of appearance of its particular nationhood.”

During 1935 the SS and its security arm the SD took an increasing role in policy towards the Jews, but the policy remained pro-Zionist: for example27ibid., p. 55. assimilationist Jewish speeches and activities were banned, while Zionist ones were encouraged. For several years Reich authorities had an especially close relationship with the ‘Revisionist’ Zionist group Staatszionisten led by Georg Kareski, who commented approvingly28ibid., p. 56. ‘Revisionist’ in this context has of course nothing to do with ‘historical revisionism’. The ‘Revisionist Zionists’ were the faction developed by Vladimir Jabotinsky during the mid-1920s in opposition to the mainstream Zionist leaders, and demanding rapid progress towards a sovereign Jewish state with maximum territory. At first pro-British, the Revisionists became increasingly anti-British after 1939. on the Nuremberg racial laws of 1935:

“For many years I have considered a clear separation of the cultural affairs of two peoples living together in one society as necessary for peaceful coexistence and have for a long time supported such a separation, which is based on respect for the alien culture. The Nürnberg Laws of 15th September 1935, apart from their constitutional provisions, seem to me to lie entirely in the direction of just such a mutual respect for the separateness of each people. The interruption of the process of dissolution in many Jewish communities, which had been promoted through mixed marriages, is from a Jewish point of view entirely welcome. For the establishment of a Jewish national existence in Palestine, these factors, religion and family, have a decisive significance.”

Soon after passage of the Nuremberg racial laws, on 26th September 1935 an article in the SS newspaper Die Schwarze Korps stated an unambiguously pro-Zionist position:29ibid., p. 57.

“In the context of its Weltanschauung, National Socialism has no intention of attacking the Jewish people in any way. On the contrary, the recognition of Jewry as a racial community based on blood, and not as a religious one, leads the German government to guarantee the racial separateness of this community without any limitations. The government finds itself in complete agreement with the great spiritual movement within Jewry itself, the so-called Zionism, with its recognition of the solidarity of Jewry throughout the world and the rejection of all assimilationist ideas. On this basis, Germany undertakes measures that will surely play a significant role in the future in the handling of the Jewish problem around the world.”

Kareski’s Staatszionisten were never more than a marginal force, and the increasingly anti-German activities of the worldwide ‘Revisionist’ Zionist movement under Vladimir Jabotinsky eventually led to the end of the SS’s cooperation with the Staatszionisten and the group’s banning in 1938.30ibid., p. 242. See also H. Levine, ‘A Jewish Collaborator in Nazi Germany: The Strange Career of Georg Kareski, 1933-37’, Central European History, Vol. 8 No. 3, September 1975, pp. 251-281. Reich authorities also permitted the far more influential Jewish Agency (Zionism’s official representatives under the British Mandate) to send instructors from Palestine (including teachers of Hebrew) to help coach prospective emigrants. The SD’s Jewish department liaised with Zionist intelligence officers including the Haganah’s Feivel Polkes,31ibid., pp. 62-64. who held talks with Adolf Eichmann in Berlin, and there is evidence that during 1935-36 the Haganah was secretly supplied with a consignment of Mauser pistols from Germany.

The crucial point however is that German policy began to change during the summer of 1937, after a British Royal Commission under Lord Peel recommended that Palestine should be partitioned into Jewish and Arab States (still under British aegis). At this point Zionism ceased to be merely a convenient channel for removing Jews from the Reich, and took on the potential of a serious focal point for World Jewry’s ambitions. Even before the Peel Commission reported, Walter Hinrichs of the German Foreign Office32ibid., p. 114. was warning on 9th January 1937 of the dangerous implications inherent in a Jewish State:

“In this connection it must be observed that a Jewish State in Palestine would strengthen Jewish influence throughout the world to unpredictable heights. Just as Moscow is the centre for the Comintern, Jerusalem would become the centre of a Jewish world organization that could work through diplomatic channels, as Moscow does.”

Hinrichs recommended that German officials should convey this opinion to London, with a view to influencing British policy in an anti-Zionist direction.

Based on the (correct) predictions of some German Foreign Office experts that the Peel Commission would recommend some form of Jewish State in Palestine, Foreign Minister von Neurath33ibid., p. 121. similarly informed his diplomats in London, Baghdad and Jerusalem on 1st June 1937:

“The establishment of a Jewish State or a Jewish-controlled state organization under British Mandate authority is not in the German interest, for a Palestine state could not absorb world Jewry, but would provide instead an additional, internationally recognised power base for international Jewry, rather like the Vatican state for political Catholicism or Moscow for the Comintern.

“There exists a German interest in strengthening the Arabs as a counterweight against the constantly growing power of Jewry.”

For some time during 1937-38 there were competing views on Zionist policy within the Third Reich’s bureaucracy, even while the ‘anti-semitic’ Polish and Romanian governments continued to support Zionism 100% as a means of resettling their Jewish populations. In July 1937 Hitler himself took what one might consider the middle ground in this dispute. His fundamental policy was to promote Jewish emigration from Germany, and his policy in 1937 was that Palestine should be explored alongside all other possible destinations.34ibid., p. 135.

Despite the ‘Arab Revolt’ and consequent developments in British policy making it hopelessly impractical for Zionism to serve as a means by which to achieve the main ‘territorial solution’ to Germany’s Jewish problem, in January 1938 Hitler repeated his decision in favour of pursuing the Zionist channel to the greatest extent feasible, and there is evidence35ibid., p. 142. that to some degree he still favoured this policy as late as July 1939.

Even after the so-called Kristallnacht of November 1938, the SD and Gestapo swiftly acted36ibid., p. 160. to reinstate the Zionist office or Palästinaamt in Berlin and promoted illegal (from the British standpoint) emigration schemes into the Mandate during 1938-40 (to the extent that it was possible to circumvent British restrictions). In his memoir Open the Gates (Atheneum, 1975), Mossad operative Ehud Avriel recalled:37ibid., p. 161.

“In pre-war Germany, these operations were neither illegal nor secret. The Gestapo office directly across the street from our own knew exactly where we were and what we were doing. The illegality began only at the shores of Palestine with the British blockade.”

SD head Reinhard Heydrich confirmed38ibid. during an official conference on the Jewish question convened by Hermann Göring three days after Kristallnacht that his SD officers in Austria had provided Haganah’s newly created illegal immigration unit – Mossad LeAliyah Bet – with training camps to assist these prospective emigrants.

After World Zionist organisations had begun, in 1939, their overt and covert activities for the British and later Allied war effort, it was inevitable that the Third Reich’s policy towards the Zionist movement would change, and move more in line with the negative views already expressed by the German Foreign Office during 1937 (see above). In wartime it was similarly inevitable that policy on Palestine and the broader Middle East would (in common with every other policy) be subordinate to primary military objectives. In this context the sensible German policy was at times to court Arab opinion (and therefore denounce Zionists, whose world organisations were explicitly hostile to Germany in any case); but at other times to cooperate secretly with some Zionist individuals and groups for specific purposes (including that of causing confusion and division for the British Mandate).

What remained consistent throughout was the so-often overlooked policy objective for a “territorial final solution” to the Jewish question. The phrase “territorial final solution” (territoriale Endlösung) was used by Heydrich in a letter to Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop on 24th June 1940. As Faurisson consistently pointed out, the word ‘territorial’ is almost always omitted when exterminationist historians use the phrase ‘final solution’ as a synonym for the ‘Holocaust’.

Yet no serious examination of National-Socialist policy towards Zionism can evade the fact that this policy was subject to change for various reasons, as a result partly of debate within the bureaucracy, and partly of bolstering by considerations of Realpolitik.

Is it not possible that Hitler over the course of more than two decades simply changed his mind – or at least entertained different theories about the Jewish Question (especially when ‘thinking aloud’ as in The Testament – if genuine)? Perhaps even that he had moved from the racial view of Jewry in Mein Kampf, to something closer to the neo-Hegelian view developed in recent years by Horst Mahler in Das Ende der Wanderschaft (whose English translation is soon to be published)?

Not for Nilsson, whose anti-Hitler certainties are so rigid that he cannot imagine why Trevor-Roper changed his own mind about the Führer’s character between writing his early classic The Last Days of Hitler (1947) and his introductory essay for Hitler’s Table Talk (1953) entitled ‘The Mind of Adolf Hitler’.

In the latter, Trevor-Roper criticised two eminent fellow historians39H.R. Trevor-Roper, ‘The Mind of Adolf Hitler’, introductory essay to Hitler’s Table Talk (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1953), p. vii. (the Zionist Jew Sir Lewis Namier and the Hitler biographer Alan Bullock) who had, he wrote, dismissed Hitler as a “charlatan, …a mere illiterate, illogical, unsystematic bluffer and smatterer, …a diabolical adventurer animated solely by an unlimited lust for personal power.”

On the contrary, Trevor-Roper maintained40ibid., pp. viii-ix. (to Nilsson’s dismay):

“We should, I think, recognise it as one sign of the genius of Hitler that he, twelve years earlier, when it seemed far more improbable, appreciated the hope of such an empire and believed – correctly as it proved – both that it could be built and that he, though then a solitary demobilised corporal, could be its builder. I have laboured this point because I wish to maintain – contrary, as it appears, to all received opinion – that Hitler had a mind. It seems to me that whereas a mere visionary might, in 1920, have dreamed of such a revolution, and whereas a mere adventurer might, in the 1930s, have exploited such a revolution (as Napoleon exploited the French Revolution which others had made), any man who both envisaged and himself created both a revolution as a means to empire and an empire after revolution, and who, in failure and imprisonment, published in advance a complete blueprint of his intended achievement, in no significant point different from its ultimate actual form, simply cannot be regarded as either a mere visionary or a mere adventurer. He was a systematic thinker and his mind is, to the historian, as important a problem as the mind of Bismarck or Lenin.”

When providing an introduction for The Testament41H.R. Trevor-Roper, ‘Introduction’ to Genoud (ed.), The Testament, pp. 1-2. six years later, Prof. Trevor-Roper made a similar point which – though adorned with obligatory offensive adjectives that would never be applied to any other historical figure – again resists once-prevalent historical tendencies to dismiss or belittle the Führer:

“What a mind Hitler had! Surely we cannot deny that. It is easy to be disgusted by it. It was vulgar and violent, coarse, cruel and horrible, filled with festering litter and old lumber from his rancorous, seedy past; and yet it was also – if we can see past this obvious and odious furniture – a mind of extraordinary power: it could clarify as well as simplify, illustrate as well as distort, make the future as well as deform the past. To deny Hitler’s mental power, to say (as some say) that he was mere froth casually thrown up by the swirling waters of social change, seems to me a desperate gesture. Even if we do not accept Hitler’s own estimate of himself as a unique historical phenomenon, a phoenix in human history, born to transform, alone in a single lifetime, the history of the world, we must yet admit that he did what no other man in our history has done. He devised, made and carried out a great revolution from start to finish, from nothing to world empire. Other great revolutions have regularly devoured their children. Hitler alone was always a devourer, never devoured. He was the Rousseau, the Mirabeau, the Robespierre, the Napoleon of his revolution: its Marx, its Lenin, its Trotzky, its Stalin. In character and mentality he may have been far inferior to most of these men, but at least he did what none of them did: he controlled his revolution through all its stages, even in defeat. This alone argues a remarkable understanding of the forces with which he conjured. He may have been a hideous historical phenomenon, but at least he was an important historical phenomenon, and we cannot afford to pass him by.”

By 1950s standards Trevor-Roper’s comments were sufficiently ‘anti-Nazi’ – especially when written by someone with his distinguished record of service to wartime British intelligence. But by 21st century standards Nilsson finds Trevor-Roper lacking. Sixty or seventy years on, the ‘Holocaust’ must take centre stage and it is dangerous to suggest that there is historical value in examining Hitler’s ideas on their own merits. For today’s scholars, he must at all times be viewed through an Auschwitz prism.

Imagine (for example) how an Englishman might (without such a Holocaustian bias) respond to the following prophetic passage from The Testament,42Genoud (ed.), The Testament, pp. 32-34. recording Hitler’s reflections on 4th February 1945:

“If fate had granted to an ageing and enfeebled Britain a new Pitt instead of this Jew-ridden, half-American drunkard [i.e. Churchill], the new Pitt would at once have recognized that Britain’s traditional policy of balance of power would now have to be applied on a different scale, and this time on a worldwide scale. Instead of maintaining, creating and adding fuel to European rivalries Britain ought to do her utmost to encourage and bring about a unification of Europe. Allied to a united Europe, she would then still retain the chance of being able to play the part of arbiter in world affairs.

“Everything that is happening makes one think that Providence is now punishing Albion for her past crimes, the crimes which raised her to the power she was. The advent of Churchill, at a period that is decisive for both Britain and Europe, is the punishment chosen by Providence. For the degenerate élite of Britain, he’s just the very man they want; and it is in the hands of this senile clown to decide the fate of a vast empire and, at the same time, of all Europe. It is, I think, an open question whether the British people, in spite of the degeneration of the aristocracy, has preserved those qualities which have hitherto justified British world domination. For my own part, I doubt it, because there does not seem to have been any popular reaction to the errors committed by the nation’s leaders. And yet there have been many occasions when Britain could well have boldly set forth on a new and more fruitful course.

“Had she so wished, Britain could have put an end to the war at the beginning of 1941. In the skies over London she had demonstrated to all the world her will to resist, and on her credit side she had the humiliating defeats which she had inflicted on the Italians in North Africa. The traditional Britain would have made peace. But the Jews would have none of it. And their lackeys, Churchill and Roosevelt, were there to prevent it.

“Peace then, however, would have allowed us to prevent the Americans from meddling in European affairs. Under the guidance of the Reich, Europe would speedily have become unified. Once the Jewish poison had been eradicated, unification would have been an easy matter. France and Italy, each defeated in turn at an interval of a few months by the two Germanic powers, would have been well out of it. Both would have had to renounce their inappropriate aspirations to greatness. At the same time they would have had to renounce their pretensions in North Africa and the Near East; and that would have allowed Europe to pursue a bold policy of friendship towards Islam. As for Britain, relieved of all European cares, she could have devoted herself to the wellbeing of her Empire. And lastly, Germany, her rear secure, could have thrown herself heart and soul into her essential task, the ambition of my life and the raison d’être of National Socialism – the destruction of Bolshevism. This would have entailed the conquest of wide spaces in the East, and these in turn would have ensured the future wellbeing of the German people.”

The Testament then does not show Adolf Hitler as being dogmatically racist or dogmatically anti-colonialist, just as he was neither dogmatically pro-Zionist nor anti-Zionist. Rather he takes a nuanced view – and we should recognise that The Testament (if genuine) shows him ‘thinking aloud’:43ibid., p. 34.

“…We were ready to throw our forces into the scales for the preservation of the British Empire; and all that, mark you, at a time when, to tell the truth, I feel much more sympathetically inclined to the lowliest Hindu than to any of these arrogant islanders. Later on, the Germans will be pleased that they did not make any contribution to the survival of an out-dated state of affairs for which the world of the future would have found it hard to forgive them. We can with safety make one prophecy: whatever the outcome of this war, the British Empire is at an end. It has been mortally wounded.”

On 7th February 1945 (during the same monologue quoted by Prof. Faurisson) Hitler appears to acknowledge colonialism’s “one instance of apparent success” but points out that this “success” was in creating the “monster which calls itself the United States”. He continues:44ibid., p. 45.

“And monster is the only possible name for it! At a time when the whole of Europe – their own mother – is fighting desperately to ward off the bolshevist peril, the United States, guided by the Jew-ridden Roosevelt, can think of nothing better to do than to place their fabulous material resources at the disposal of these Asiatic barbarians, who are determined to strangle her. Looking back, I am deeply distressed at the thought of those millions of Germans, men of good faith, who emigrated to the United States and who are now the backbone of the country. For these men, mark you, are not merely good Germans, lost to their fatherland; rather, they have become enemies, more implacably hostile than any others. The German emigrant retains, it is true, his qualities of industry and hard work, but he very quickly loses his soul. There is nothing more unnatural than a German who has become an expatriate.”

Somewhat contradicting his own words of just three days earlier, Hitler now says:45ibid., p. 46.

“Since colonization is not an activity which Germans feel called upon to pursue, Germany should never make common cause with the colonizing nations and should always abstain from supporting them in their colonial aspirations. What we want is a Monroe doctrine in Europe. ‘Europe for the Europeans!’, a doctrine, the corollary of which should be that Europeans refrain from meddling in the affairs of other continents.

“The descendants of the convicts in Australia should inspire in us nothing but a feeling of supreme indifference. If their vitality is not strong enough to enable them to increase at a rate proportionate to the size of the territories they occupy, that is their own look out, and it is no use their appealing to us for help. For my own part, I have no objection at all to seeing the surplus populations of prolific Asia being drawn, as to a magnet, to their empty spaces. Let them all work out their own salvation! And let me repeat – it is nothing to do with us.”

A broadly similar point is made on 24th February 1945 when discussing US policy:46ibid., pp. 91-92.

“The fact that neither we nor they have any colonial policy is yet another characteristic which should unite us.”

Yet again this section of The Testament partly contradicts another section wherein Hitler implies that Britain was a natural ally of Germany because it did have the Empire, but if one allows that he is ‘thinking aloud’ there appears a consistent line that Germany itself should focus on a land-based rather than a maritime/imperialist policy. He states that “the Germans have never felt the imperialist urge” and deprecates the brief exception under the Kaiser in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which he sees as an unfortunate historical accident:

“Our defeat in 1918 had at least the fortunate consequences that it stopped us from pursuing the course into which the Germans had foolishly allowed themselves to be led, influenced by the example of the French and the British and jealous of a success which they had not the wit to realize was purely transitory.

“It is to the credit of the Third Reich that we did not look back with any nostalgia to a past that we have discarded.”

Earlier during the 14th February section of The Testament, Hitler criticised his own Foreign Office47ibid., pp. 60-62. for their indulging of French ‘traditionalists’ and their imperial dreams:

“Our greatest political blunder has been our treatment of the French. We should never have collaborated with them. It is a policy which has stood them in good stead and has served us ill…

“Our obvious course should have been to liberate the working classes and to help the workers of France to implement their own revolution. We should have brushed aside, rudely and without pity, the fossilized bourgeoisie, as devoid of soul as it is denuded of patriotism. Just look at the sort of friends our geniuses of the Wilhelmstrasse [i.e. the German Foreign Office] have found for us in France – petty, calculating little profiteers, who hastened to make love to us as soon as they thought that we were occupying their country in order to safeguard their bank balances – but who were quite resolved to betray us at the first possible opportunity, provided always that no danger to themselves was involved!

“We were equally stupid as regards the French colonies. …Never, at any price, should we have put our money on France and against the peoples subjected to her yoke. On the contrary, we should have helped them to achieve their liberty and, if necessary, should have goaded them into doing so. There was nothing to stop us in 1940 from making a gesture of this sort in the Near East and in North Africa. In actual fact our diplomats instead set about the task of consolidating French power, not only in Syria, but in Tunis, in Algeria and Morocco as well. Our ‘gentlemen’ obviously preferred to maintain cordial relations …with a chorus of musical comedy officers, whose one idea is to cheat us, rather than with the Arabs, who would have been loyal partners for us.

“…In reality there was one possible policy to adopt vis-à-vis France – a policy of rigorous and rigid distrust.”

In fairness to the brave fighters of the Charlemagne Division – and to Prof. Faurisson’s half-French ancestry! – I should add that on 15th February 1945 The Testament records Hitler as saying:48ibid., p. 68.

“I have never liked France or the French, and I have never stopped saying so. I admit, however, that there are some worthy men among them. There is no doubt that, during these latter years, quite a number of Frenchmen supported the European conception with both complete sincerity and great courage. And the savagery with which their own countrymen made them pay for their clear vision is of itself a proof of their good faith.”

Another relevant observation on colonialism comes in The Testament’s entry for 17th February, where the Führer observes:49ibid., pp. 70-72.

“Our Italian ally has been a source of embarrassment to us everywhere. It was this alliance, for instance, which prevented us from pursuing a revolutionary policy in North Africa. In the nature of things, this territory was becoming an Italian preserve and it was as such that the Duce laid claim to it. Had we been on our own, we could have emancipated the Moslem countries dominated by France; and that would have had enormous repercussions in the Near East, dominated by Britain, and in Egypt. But with our fortunes linked to the Italians, the pursuit of such a policy was not possible. All Islam vibrated at the news of our victories. The Egyptians, the Iraqis and the whole of the Near East were all ready to rise in revolt. Just think what we could have done to help them, even to incite them, as would have been both our duty and in our own interest! But the presence of the Italians at our side paralysed us; it created a feeling of malaise among our Islamic friends, who inevitably saw in us accomplices, willing or unwilling, of their oppressors…

“In this theatre of operations, then, the Italians prevented us from playing our best card, the emancipation of the French subjects and the raising of the standard of revolt in the countries oppressed by the British. Such a policy would have aroused the enthusiasm of the whole of Islam.

“…Further, this futile policy has allowed those hypocrites, the British, to pose, if you please, as liberators in Syria, in Cyrenaica and in Tripolitania.”

Naturally the above sections on colonialism could be seen as evidence upholding Nilsson’s argument that Genoud forged The Testament to support his own views and connections in the Middle East, though we should note that the argument is slightly anachronistic: in Genoud’s era the most significant anti-Zionist forces in the Arab world were the secular and nationalist (and certainly not Islamist) governments of Egypt and Syria, plus the partly Christian Palestinian liberation movements that were also partly under the influence of Moscow, and again certainly not Islamist. Yet in The Testament, Adolf Hitler speaks repeatedly of Islam and regrets missed opportunities for a German-Islamic alliance: surely a Genoud ‘forgery’ would have been more likely to speak of ‘Arabs’ than ‘Moslems’? At no point in his 400-page book on the Table Talk and Testament does Nilsson mention Hitler’s comments on Islam.

Now we come to the section of The Testament that was discussed in a secret British government file, only released at the start of 2021. And it is here that we find fragments of evidence that help to undermine Nilsson’s case, even though they fall a long way short of establishing The Testament’s authenticity.

A very large part of Nilsson’s book (and of his earlier articles in academic journals50Mikael Nilsson, ‘Hugh Trevor-Roper and the English Editions of Hitler’s Table Talk and Testament’, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 51 No. 4, 2016; and ‘Constructing a Pseudo-Hitler? The question of the authenticity of Hitlers politisches Testament’, European Review of History, Vol. 26 No. 4, 2019.) is devoted to attacking not only François Genoud – the proud National-Socialist mainly responsible for the publication of both The Testament and the earlier Hitler’s Table Talk – but also Trevor-Roper, the eminent British historian and wartime intelligence officer who effectively ‘authenticated’ both texts and wrote introductions to their various editions.

For Nilsson, Trevor-Roper was not merely mistaken in each case, but at the very least culpably lazy and motivated by financial gain as well as the ‘glory’ of being associated with best-selling texts widely promoted in the press. Nilsson uses damning language throughout, naturally about Genoud who as a National-Socialist can easily be dismissed by a politically-correct 21st century writer as “a liar and a confidence trickster”, but also about his British collaborator:51Nilsson, Hitler Redux, p. 385.

“I have shown that British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper had a very central role in the publication of all of Genoud’s documents and that Trevor-Roper consistently refrained from telling his readers about the many and serious source-critical problems with the sources that he validated. He benefited financially from this practice and admitted in private correspondence that he did not question Genoud’s texts in public because he wished to be the one that Genoud turned to the next time he had a text for publication.”

Nilsson makes an important distinction between the two texts. He regards Hitler’s Table Talk as unreliable rather than forged, in the sense that “for the most part” it contains “memoranda of statements that Hitler made at some point or another in his wartime HQs” – but also containing some misunderstandings and interpolations, so requiring a detailed study to untangle the reliable parts from the unreliable.

However he unequivocally describes The Testament as “a forgery”. As pointed out above, some of Nilsson’s assertions on this point seem over-dogmatic and rooted in a priori assumptions about statements that in his view “Hitler reasonably cannot have made”. But what of the core relationship between Trevor-Roper and Genoud, and the circumstances that led to The Testament’s publication?

As a seventeen-year-old student in 1932 François Genoud (half-French and a quarter-English) met Adolf Hitler at a hotel in Bad Godesberg and shook the future Führer’s hand.52David Lee Preston, ‘Hitler’s Swiss Connection’, Philadelphia Inquirer, 5th January 1997. He remained an ardent National-Socialist for the rest of his life, first as an activist in the Swiss National Front, then as an agent for the Abwehr, Germany’s military intelligence service, working for senior Abwehr officer and future Interpol chief Paul Dickopf and, eventually, as an intermediary for close aides of Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS. There are many colourful allegations about his role in smuggling assets out of Germany at the end of the war, though such stories concerning the likes of ODESSA remain controversial and often unprovable.

Postwar Genoud became both a banker and business networker with excellent Middle Eastern connections, and a broker for National-Socialist veterans with documents to sell or publish. According to one document in the only MI5 file on Genoud so far released,53KV 2/3708. he was involved during the 1950s in numerous Middle Eastern and North African arms deals and was president of the Association Internationale des Amis du Monde Arabe Libre, whose German branch was headed by Hans Rechenberg, “a deep-dyed Nazi up to 1945 and a close friend of the Nazi minister Funk, who was executed by the Allies”. This latter sentence shows horrible confusion on the part of someone in MI5. Walther Funk was not executed (he died of natural causes in 1960): as we shall see, Funk, Rechenberg and Genoud were the three key individuals involved in publication of The Testament.

MI6 reported54Extract from MI6 letter, 10th September 1956, KV 2/3708, s.9a. that one of its German informants was visited by Genoud and Rechenberg during the second week of August 1956:

“Genoud was introduced as a Swiss citizen and a great friend of Germany. Source gathered from subsequent conversation that this friendship with Germany entailed adoration of all things Nazi.

“Rechenberg said that they came to see source in order to obtain his advice and financial support in founding an organisation to be named ‘Friends of the Arab Peoples’ (or Nations). The organisation which would be founded in West Germany in Frankfurt am Main would form part of an international organisation of the same name. The policy of the organisation would be pro-Arab, pro-German, anti-Israel and anti-British.”

It must be borne in mind that the above developments coincided with the Suez crisis, i.e. at a time when Britain had formed a semi-secret alliance with Israel and France against Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser, who in this period had large support throughout the Arab world and was backed by National-Socialist networks including German aerospace scientists.

Trevor-Roper’s relationship with Genoud dated back to 1952:55Adam Sisman, Hugh Trevor-Roper: The Biography (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2010), pp. 214-216. they first met in Lausanne and then in Paris, together with the Jewish publisher George Weidenfeld in connection with the project for Hitler’s Table Talk, which Weidenfeld published the following year with an introduction by Trevor-Roper. For this introduction and a modest amount of editorial work, Weidenfeld paid Trevor-Roper a fee of 300 guineas,56ibid. a handsome sum but hardly the sort of fortune for which one of the greatest historians of his era would trade his reputation. (300 guineas – £315 – in 1953 was roughly equivalent to £10,000 today.)

The following year another deal involving Genoud and Weidenfeld (this time for The Bormann Letters, a volume of correspondence between Martin Bormann and his wife Gerda) ultimately netted Trevor-Roper another 300 guineas.

During the autumn of 1958 Trevor-Roper travelled to Paris and met Genoud again to discuss what became The Testament. His biographer acknowledges57ibid. p. 302 that (although Trevor-Roper’s main scholarly interest was in the 17th century not the 20th) his recognised expertise regarding Adolf Hitler (dating from his immediate postwar researches commissioned by military intelligence and the subsequent and highly successful book The Last Days of Hitler) provided substantial income:

“Hugh’s role was to authenticate the documents; without his imprimatur they were much less valuable. There was a voracious appetite for such material in many different countries, even though the content was often flimsy or banal. And even when the authenticity of the documents was not in question, Hugh benefited from a widespread sense that it was unseemly to publish such material without a scholarly commentary to set it in context. He was the first man to whom newspaper, magazine and book publishers would turn for such a purpose, and was thus able to command substantial sums for his commentaries and introductions; his letters to his agent show that he was alive to his worth, and determined to exploit it to the full.”

One can see how a determined 21st century cynic might take the view that even Oxford’s Regius Professor of Modern History would allow his judgment to be affected by such lucre. Unfortunately for Trevor-Roper he is not only a ‘dead white male’, but one whose type is especially likely to arouse wokerati contempt – a fox-hunting Tory, married to the titled daughter of a Field-Marshal.