(An earlier version of this article appeared at a blog linked to the Renouf defence campaign at https://modeltrial.blogspot.com/)

At the eleventh hour German prosecutors in October 2020 called off a criminal trial for ‘holocaust denial’. The reasons for this reversal – in a case that had been prepared for two and a half years – are still mysterious. But it appears that one motive was to avoid embarrassment over an aspect of Second World War history that had remained secret until uncovered by researchers for the defence team.

Defence evidence in the trial of Australian-born international model and television commercials actress Lady Michèle Renouf would have exposed the existence of a previously unknown British spy inside the Third Reich.

***

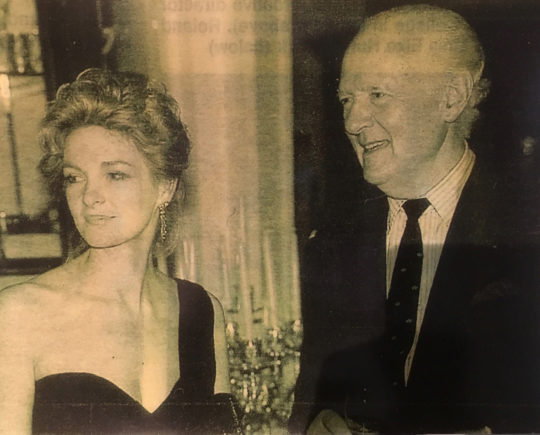

Hermann Abs was the most powerful German banker of the 20th century, despite his career having flourished under Adolf Hitler. Had the trial of Lady Renouf proceeded in Dresden, the Abs case would inevitably have been highlighted, because he was one of the closest friends and colleagues of her late husband Sir Francis Renouf (aka “Frank the Bank”): they are shown together in the photo below.

This would have been a double disaster for German state prosecutors.

The most serious embarrassment would have come from the Abs story being examined in court. We reveal here some of the devastating facts that would have been presented in Dresden.

In this abbreviated extract from a forthcoming book by Peter Rushton, who was a research consultant to the Renouf defence team, we uncover a secret that lasted for almost eighty years – the identity of a German-Jewish spy inside the Third Reich, and his role in the postwar rehabilitation of financial godfather Hermann Abs.

May 1990. The attacks had been shrugged off for decades, but 88-year-old Hermann Abs knew the sharks were now circling. Yet another cycle of ‘Holocaust hype’ was being boosted worldwide – almost half a century after the Second World War – with construction of memorials and enacting of laws that turned ‘Holocaust’ history into an unchallengeable quasi-theological edifice. Researchers, scientists, publishers and even lawyers who dared to disagree were starting to be dragged into court, and would soon face heavy fines or even jail sentences.

Actual participants in the ‘Holocaust’ were by now few and far between, so professional ‘nazi-hunters’ were mainly reduced to pursuing small fry, such as teenage Ukrainians who had guarded a concentration camp. The UK was midway through passing a new law that would allow the prosecution of elderly Soviet and East European émigrés who had taken refuge in Britain postwar, despite their ‘crimes’ having taken place well outside UK jurisdiction and prosecution ‘evidence’ coming from the now collapsing and discredited Soviet bloc. In May 1991 this War Crimes Act entered the UK statute book.

Hermann Abs himself was one of the few surviving (indeed flourishing) big name players from the Third Reich – he was described by David Rockefeller as “the most important banker of our time”. A biographical summary prepared for the chief of the CIA’s European Division in December 1974 quoted Rockefeller’s assessment and added that while Abs “holds no governmental positions his influence is enormous and dates back to his successful leadership in 1952 of the German Delegation which regulated the post-war German reparation question and set the basis for the FRG [West Germany] to regain its sovereignty in 1955. He was awarded the Federal Service Cross First Class for this achievement and repeatedly declined Cabinet posts offered by Adenauer and succeeding Chancellors. …As a rough comparison he might be called the Bernard Baruch of Germany.”

Yet during that first weekend of May 1990 a special World Jewish Congress meeting in Berlin celebrated news that this eminent financier had at last been barred (as a “nazi”) from entering the USA. Abs still held many honorary and advisory positions, and was in regular touch with old friends across the banking world including Sir Frank Renouf, the New Zealand-born tycoon who (largely thanks to his work with Abs to open up West German investment banking) had received the Federal Republic’s highest honour, the Verdienstkreuz.

Semi-retired in the Taunus Mountains of central Hesse, Abs lost nothing in practical terms by being banned from the USA, but it was a big propaganda victory for the Zionist lobby. This time they weren’t picking on the small fry: Hermann Abs was the biggest name in German finance, and arguably the most powerful individual in postwar banking.

He still had friends in the banking world: that very year his old ally Renouf visited Germany to collect a duplicate of his Verdienstkreuz (the original medal having been lost in a burglary). Sir Frank was accompanied by his new fiancée Michèle, Countess Griaznoff, an Australian-born Briton and international model who had appeared worldwide in print and television advertisements for Deutsche Post, Tchibo coffee, Nescafé, Lenthéric, Helena Rubenstein, Oil of Olay, Avon, Supradyn vitamins, Rowntree’s After Eight chocolates, Carlos I brandy, Wedgwood, Nissan cars, BMW, British Airways, ResidenSea cruises, C&A, Heinz, France Telecom, Cable & Wireless, Capital One Credit Cards, the Sunday Times, Daily Mail, Daily Mirror and many others. Speaking to the Daily Mail’s society columnist Nigel Dempster a few months later following their marriage, Sir Frank revealed that he had proposed “after a cocktail party at St James’s Palace. Her title is Russian but it doesn’t matter now – she’s Lady Renouf.”

Renouf remained a loyal supporter of Abs to the end, as did senior British bankers in his circle such as Lord Sandon (later Earl of Harrowby), deputy chairman of NatWest and Coutts. But the verdict of history was already being written. Winston Churchill said that history would be hard on his old enemy Stanley Baldwin: “I know it will, because I shall write that history.” Until now, the same has been true of Hermann Abs – to a very large extent his enemies (and the enemies of Germany) have been writing history.

Abs died in February 1994, aged 92. Five years later one of his most determined antagonists, Anglo-Jewish television journalist and historian Tom Bower, was able to dance on his grave. Millions of Daily Mail readers were treated to a full page article (accompanied by a huge photo of Abs) condemning the Deutsche Bank that he had chaired for a decade. Under the headline “The Genocide Bank”, the Mail thundered:

“As the mighty Deutsche Bank finally admits it financed Auschwitz, we reveal how two Britons conspired to protect its Nazi founder.”

Bower pulled no punches: by his account, Abs and Deutsche Bank had set out to “conspire with Adolf Hitler and Heinrich Himmler to murder thousands of innocent men and women for the benefit of the bank’s shareholders.” Half a century later, Bower boasted, “Abs’s success has been undone. His attempt to bury the past and disguise his own criminality, nearly successful in his lifetime, has been utterly destroyed.”

To a large extent Bower’s article was a rehash of his first book, Blind Eye to Murder, published in 1981 and in an updated second edition in 1995. Bower had targeted Abs on the very first page of Blind Eye to Murder, and his allegations were highlighted by The Times when serialising the book in July 1981. The latest topical addition in 1999 was that Deutsche Bank, in order to satisfy New York regulators and facilitate its $9.8 billion takeover of Bankers Trust of New York, had – as Bower candidly acknowledged – caved in to “Jewish lobby groups” and “after 54 years of adamant denials” had confessed that “their predecessors did after all partly finance the construction of Auschwitz, the Nazi concentration camp”, in what Bower described as “a monumental humiliation for the Germans”.

Hermann Abs left school in the Rhineland soon after the end of the First World War. Amid the economic and financial chaos that followed Germany’s defeat he went straight into banking rather than university, serving his first apprenticeship at the Jewish-owned Louis David bank in Bonn, then as a foreign exchange dealer in Amsterdam. He swiftly advanced during the late 1920s with the elite private bank Delbrück, Schickler, where Adolf Hitler himself later held an account containing secret donations from German business leaders. By the age of 33 Abs was a partner in Delbrück, Schickler, and before his 37th birthday in 1938 he was on the managing board of the giant Deutsche Bank, becoming head of its international operations.

As a lifelong Anglophile whose father had spent two years tutoring in Victorian England, Abs’s Catholicism also helped with the networking essential to his trade as an international banker. Without criticising his own government, he could discreetly put some distance between himself and both the earlier Protestant Prussianism of the Kaiser’s Germany, and the National Socialist new order.

This distancing suited the authorities in Berlin also, who notably showed no interest in pressuring Abs to become a member of the National Socialist Party. When leading the German side in late 1930s’ negotiations on debt repayments in London or New York, it suited all concerned that Abs was not ostentatiously ‘nazi’.

For a time Abs was seen as a protégé of Hitler’s first Reichsbank President and economics minister Dr Hjalmar Schacht, but he survived Schacht’s fall from power after 1939 and continued to extend his own influence as a director of no fewer than 45 companies during the war years. A typical Abs appearance was on 28th July 1941 at the grand 60th birthday party of Günther Quandt, an industrial magnate and arms manufacturer who was the first husband of Joseph Goebbels’ wife Magda. In his speech toasting Quandt at the dinner in Berlin’s Hotel Esplanade, Abs said: “You were able to make the successful transition to the new era in 1933 as a result of your skilful tactics and your special abilities. But your most outstanding characteristic is your faith in Germany and the Führer.”

Abs also sat on the board of directors of IG Farben, the giant chemical and pharmaceutical conglomerate. Abs’s role at Deutsche Bank and at Farben was the main reason for controversy that pursued him after 1945.

Farben had many government contracts during the Third Reich: the company’s importance to the war effort across Europe led to it being targeted for black propaganda rumours by a special subcommittee of Britain’s Political Warfare Executive. A Farben subsidiary produced Zyklon B, the cyanide-based pesticide used to destroy lice that carried the deadly disease typhus. Since typhus was especially hazardous in crowded conditions such as prisons and concentration camps, Zyklon B was extensively used in camps such as Auschwitz – but in ‘Holocaust’ mythology it has come to be assumed that Zyklon B’s purpose was to kill Jews in homicidal gas chambers.

Hence Farben was demonised and many of its directors were put on trial at Nuremberg for ‘war crimes’. Nine were convicted, including supervisory board chairman Carl Krauch who was given a six-year sentence, and Walter Dürrfeld, technical manager of IG Farben Auschwitz, who got eight years.

Similarly several leading German bankers were pursued by war crimes prosecutors. The most prominent were among the accused at the so-called ‘Ministries Trial’ at Nuremberg. Lutz Graf Schwerin von Krosigk, Minister of Economics throughout the Third Reich, who had worked very closely with Abs, was sentenced to ten years. (His granddaughter Beatrix von Storch is now a deputy leader of the anti-immigration party Alternative for Germany – AfD.) Another of Abs’s most senior colleagues, Reichsbank vice-president Emil Pühl, was jailed for five years, and Karl Rasche, director of one of Deutsche’s rivals the Dresdner Bank, for seven years.

It is inevitable therefore that historians (whether or not they are highly partisan ‘anti-nazis’) have asked: why was Hermann Abs not among the defendants? He was in fact sentenced to 15 years in absentia by a communist court in Yugoslavia, but this could be put down to Cold War propaganda against the West. Elsewhere, until the World Jewish Congress succeeded in having him banned from the USA 45 years after the war, Abs had seemed untouchable.

***

3rd May 1945: Abs swiftly vacated his suite at Hamburg’s Vierjahreszeiten (‘Four Seasons’) Hotel immediately on the city’s surrender to the British 7th Armoured Division – within hours the hotel had been converted into the new headquarters for Britain’s occupying forces.

For six weeks he prudently stayed out of sight, safely hidden at the nearby home of a friend. Yet when the British eventually tracked him down it was not to arrest him – despite his name being (for alphabetical reasons) at the very top of a list of wanted ‘war criminals’. Instead the British wanted to recruit him to help rebuild Germany’s postwar banking system!

To do so, the British had to protect Abs from their vengeful allies. A US intelligence report prepared for the War Department in March 1945 had featured Abs prominently among those financial and business leaders who “in an outstanding way thrived under National Socialism, …aided the Nazis to obtain power, …[and] shared the spoils of expropriation and conquest.”

Jewish-American attorney Col. Bernard Bernstein was a partisan supporter of the Morgenthau Plan devised by his co-racialist Henry Morgenthau, President Roosevelt’s Treasury Secretary, who aimed at the permanent destruction of Germany’s industrial and technical capacity, despite an assessment that this would mean the deaths of 40% of German civilians. Bernstein had himself been a US Treasury Department attorney before being transferred to the Army as financial adviser to Allied Commander Gen. Dwight Eisenhower. Col. Bernstein led the American effort to put Abs on trial, sending a fellow Jewish officer, Maj. Andrew Kamark to interrogate him in the British zone.

This interrogation failed to obtain any evidence on which Abs could be charged, but by the start of 1946 continuing political pressure from the Americans, including threats to leak stories about Abs to the British press, meant that he had to be purged from his directorships and jailed. Even now, held in Altona prison in Hamburg, and later at the notorious Bad Nenndorf interrogation centre during the first half of 1946, Abs was locked up not so that he could be ill-treated in any way, but so that he could be kept away from the Americans.

Predictably this saga has been interpreted repeatedly by Jewish historians and other partisan observers as a tale of “perfidious Albion” – of Britain deliberately ignoring evidence of Nazi criminality. This theme has been taken up in other contexts by Jewish polemicists attacking Britain for its postwar opposition to establishment of the state of Israel, and for recruiting Russian and Eastern European anti-communists for Cold War operations against Stalin. The late Prof. David Cesarani was especially outspoken, when campaigning for introduction of the War Crimes Act 1991: Cesarani’s first book published in 1992 condemning postwar British policy was entitled Justice Delayed: How Britain Became a Refuge for Nazi War Criminals.

These witch-hunters point in particular to Abs’s role at Deutsche Bank in the ‘Aryanisation’ of Jewish-owned banks, including Germany’s largest private bank, Mendelssohn & Co.

The anti-Abs campaign began soon after the war, led by the anti-British US Senator Guy Gillette, an infamous supporter of Jewish terrorists in Palestine. As I discovered in the course of detailed research, the anti-Abs theme was picked up through the 1950s by syndicated columnist Drew Pearson, notorious for his close ties to the Israeli lobby and his hounding of anti-Zionist US Defense Secretary James Forrestal, leading up to Forrestal’s suicide or murder in 1949. By 1981 it was the turn of Tom Bower (né Bauer), a BBC journalist and son of Czech refugees, to take up the charge against Abs, which he pursued for the next twenty years or more. And most recently Michael Pinto-Duschinsky, Oxford-educated political consultant and Hungarian rabbi’s son, has taken up the cudgel, bashing Abs years after his death as part of a campaign of outrage against two ‘nazi-linked’ donors to Oxford University, Alfred Toepfer and Gert-Rudolf Flick.

As recently as the Brexit referendum of 2016, echoes of the anti-Abs campaign resounded. Novelist and foreign correspondent Adam LeBor wrote two non-fiction books, a novel and several articles about “nazi bankers”, fuelling the notion that the European Union was in some sense a fulfilment of “old nazi” dreams of a Fourth Reich. This theory was explicitly rooted in the so-called ‘Red House Report’, supposedly an account of a secret meeting of the Third Reich’s industrial and financial elite, held at the Maison Rouge Hotel in Strasbourg on 10th August 1944. Three months later the supposed minutes of this meeting reached US military intelligence, via a French source.

According to this report, the German financial elite planned a “secure post-war foundation in foreign countries… existing financial reserves must be placed at the disposal of the party so that a strong German empire can be created after the defeat”. Front companies abroad would then carry out military research and intelligence tasks until a multinational, German-dominated empire could be rebuilt.

“Now,” the report’s author continued, “the Nazi Party stands behind the industrialists and urges them to save themselves by getting funds outside Germany and at the same time advance the party’s plans for its post-war operations.”

LeBor treated the Red House Report as accurate, and some time later his story was regurgitated by the World Jewish Congress who in 2011 became the latest to ’discover’ the Red House Report. This same yellowing paper has been sensationally ‘rediscovered’ at least three times during the last twenty-five years: by Adam Lebor in 1996; by the medical doctor and controversial historian Hugh Thomas in 2001; and by the World Jewish Congress in 2011. Yet there is no convincing evidence for its authenticity. It suited the interests of both Henry Morgenthau and the Soviet Union in the mid-1940s, and was promoted by a Soviet asset in Roosevelt’s administration, Harry Dexter White, but even those mainstream historians who willingly swallow other wartime propaganda inventions now view the Red House Report with considerable scepticism.

It remains however very attractive to some pro-Brexit propagandists, especially because of Hermann Abs’ role in promoting European unity postwar. Not only was Abs instrumental in establishing the Deutsche Mark in 1948, giving West Germany a stable currency (known outside Germany as the Deutschmark), he also became one of the leading advocates of what became the Common Market and later the European Union, and was a principal backer of Germany’s pro-European Chancellor Konrad Adenauer.

(More recently, similar confused conspiracy theorists have seized on the ‘nazi’ connection when discussing links between Hermann Abs and Klaus Schwab of the World Economic Forum.)

We can now reveal – and would have revealed in court – that the key promoter of Hermann Abs in 1946 was not some undercover SS man straight out of Frederick Forsyth’s The Odessa File, nor some reactionary British aristocrat. In fact the British occupation authorities were lobbied to press ahead with Abs’s rehabilitation by Robi Mendelssohn, a partner in the long-established Jewish banking firm Mendelssohn & Co. Reading the accounts by Tom Bower, Adam LeBor, and Michael Pinto-Duschinsky, one would assume that the Mendelssohn family were victims of brutal Nazi rapacity, facilitated by Abs, and that Robi Mendelssohn should have been first in the queue to demand Abs’s prosecution as a ‘war criminal’.

Yet in fact Mendelssohn was the prime mover insisting that Abs was the man the British should immediately get onside in a key role to rebuild postwar Germany.

Who was Robi Mendelssohn? Why was he in a position to give high-level advice to the postwar British authorities? And why has his role remained secret until now, more than 75 years after the war?

Robert von Mendelssohn (known to friends, family and MI6/MI5 officers as Robi) was born in 1902 at a palatial residence in the Grunewald district of western Berlin, built for his father Franz, head of the family bank Mendelssohn & Co. The German Kaiser Wilhelm II had fourteen years earlier granted the family the noble prefix ‘von’ in recognition of their importance to the Reich’s economy.

The Mendelssohn bank was founded in 1795 by Joseph Mendelssohn, eldest son of the philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, and until the 1920s all of its partners (including the composer’s father Abraham) were family members. The firm came to specialise in government debt and overseas trade.

Franz von Mendelssohn died in June 1935 aged 69. As his Financial Times obituary emphasised, he remained senior partner of the bank and died at his home:

“Rumours that he was interned in a concentration camp are entirely erroneous, neither he nor any member of his family ever having been in such a camp.”

His 34-year-old son Robi was now in principle head of the family and already a partner in the bank, but was regarded as more of a playboy entertainer: his role was to amuse visiting VIPs in Berlin theatres and nightclubs. Adolf Hitler had by this time been Chancellor of Germany for two and a half years, but it was three years after Franz’s death that moves were made to “Aryanise” the bank. The initial problem in 1935 came not from the National Socialist government but within the family. Both Franz and his cousin Paul von Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, a fellow partner in the bank, died during 1935. In the ensuing family reshuffle Franz’s widow Marie was registered as a ‘managing partner’ but Paul’s widow Elsa was not.

In the meantime Robi cemented his credentials with the government by volunteering in 1936 for four months basic training in the German Army, and in 1938 he married the architect Liselotte von Bonin. It was during that summer – five years into National Socialism – that Mendelssohn’s bank began to reach the end of its almost 150-year history. Even then, records show that the government’s preferred solution was to transfer Jewish-owned shares to Robi, who classed as a mischling, or half-Jew.

A major issue here was that the bank held about 27 million Reichsmarks in “lines of credit” for overseas trade. During the financial crisis of 1931 these lines of credit had been frozen and were subject to renegotiation every year under the terms of the ‘Standstill Agreement’. Hermann Abs was one of the main German negotiators. In principle the bank’s proprietors were responsible and were any of the proprietors to withdraw, foreign creditors could demand immediate payment in foreign currency, which would mean seizure of assets.

By taking over Mendelssohn’s, any German bank would be doing the Jewish partners a favour not robbing them, as these Jewish partners would then be freed from the threat of having their foreign assets seized. A further issue during the takeover was that non-Jewish employees of the bank were concerned that the partners were getting a good deal while leaving the employees vulnerable to pay cuts, redundancy or threats to their pensions (a situation familiar to every reader whose employers have been taken over). Jewish employees as opposed to the partners and owners were of course in a much worse position: they were dismissed at the end of 1938 when the bank went into liquidation.

It became clear during 1938 that the preferred solution was for Deutsche Bank to take over Mendelssohn’s, and Abs handled the negotiations. Among the ‘crimes’ commonly attributed to Hermann Abs was this Deutsche Bank takeover of Mendelssohn & Co., the largest private bank in Germany, as well as its Amsterdam branch in 1940. As is standard in such cases, the tale is of innocent Jewish businessmen having their property confiscated, their art collections seized by the state. However the truth is that the Amsterdam branch of Mendelssohn’s, which had become a separate entity under the control of Jewish crook Fritz Mannheimer, had already become insolvent in August 1939 – eight months before the German invasion of the Netherlands.

As noted above, the position of Mendelssohn’s Bank in Germany was far more complicated, mainly due to its international debt obligations. From 1938 to 1943 it continued to operate as “Mendelssohn in Liquidation”, with Robi as the most important family partner – indeed by 1942 the sole partner – and by 1943 the liquidation was almost completed, with Deutsche Bank having absorbed almost all its assets and liabilities.

Meanwhile several other family members were given financial compensation for the value of their shareholdings in the liquidated bank, and very importantly were freed from their obligations regarding its debts. These included Robi’s brother-in-law Paul Kempner, a former partner in the bank who emigrated to the USA in 1939. Kempner worked postwar as treasurer of an association formed to provide financial assistance for relatives of anti-Hitler conspirators – the American Committee to Aid Survivors of the German Resistance of July 20. Kempner had been an official of the liberal German Democratic Party during the Weimar Republic, and at the end of the Weimar years was Germany’s representative on the Finance Committee of the League of Nations.

Unlike his brother-in-law Kempner, however, Robi was not overtly involved in politics.

For most of the decade between his father’s death and the end of the war, therefore, Robi Mendelssohn continued to play an important role in what had been Germany’s largest private bank, especially in regard to international trade (limited of course after 1939 to neutral and German-allied countries).

The German government evidently felt that Robi Mendelssohn was one half-Jew who could be trusted. They were wrong.

In the summer of 1943 senior MI6 officer John Cordeaux reported to the Foreign Office (in a document revealed here for the first time) that during a trip to Stockholm, Mendelssohn had made contact with the MI6 representative in the Swedish capital, Harry Carr.

Carr was a veteran MI6 officer who first worked for British intelligence in Russia soon after the Bolshevik revolution. From 1928 to 1941 he had been in charge of the important MI6 station in Helsinki, mainly focused on anti-Soviet operations, then relocated to Sweden after Finland joined the German side in 1941.

This sensational contact from a high-level Berlin source had to be handled at top level within MI6 and the Foreign Office, whose head Sir Alexander Cadogan had written to MI6 chief Sir Stewart Menzies only a few weeks earlier about the extreme sensitivity of such operations:

“The danger grows in proportion as the enemy national concerned is a person of standing in his own country, and I would say that no direct contact whatever should be made (without prior reference to myself) with any really prominent enemy national, such as a Cabinet Minister, a General or a senior official. These last are precisely the sort of contacts that are likely to become known and that are most likely to arouse Russian suspicions; and even if it ever seemed desirable to authorise a contact of this kind, it would, I think, simultaneously be necessary to inform the Russians of it and probably the Americans as well.”

Hence Cordeaux felt it necessary to inform Cadogan (through his intelligence liaison officer Peter Loxley) about the Mendelssohn case:

“With reference to Sir Alexander Cadogan’s personal and secret letter to my Chief of 18th June, and his letter C/3646 in reply, one of the members on the staff of our late representative in Helsinki, now working in Stockholm, has contacted Robert Mendelsohn [sic], a member of the German Mendelsohn Banking Firm who has been visiting Stockholm on official German foreign exchange business.

“This is a most interesting and valuable contact which we have directed the officer concerned to follow up. Our officer handling this contact is an experienced, able and very discreet man, and the contact will in any case be supervised by our late Helsinki representative whom you know but, as Mendelsohn is a man of some importance, I thought it best to inform you in accordance with the above-quoted letters.”

After this initial contact with MI6, Mendelssohn made two further visits to Stockholm during the second half of 1943, and one in 1944, on each occasion meeting with MI6 and with an unnamed American diplomat (probably OSS officer Francis Cunningham). He appears to have been partly acting as an intermediary on behalf of German military intelligence officer Georg Hansen, right-hand man to Abwehr chief and arch-plotter Admiral Wilhelm Canaris.

In 1944 Hansen became deputy chief of the SS intelligence organisation RSHA, where he continued working with anti-Hitler conspirators who attempted to assassinate the Führer in the failed Stauffenberg bomb plot of 20th July 1944. Hansen was arrested on 22nd July, convicted, and hanged on 8th September 1944.

Another influential associate of Mendelssohn’s was the lawyer Carl Langbehn, regarded by historians as in some sense an associate of Heinrich Himmler. Langbehn had preceded Mendelssohn to Stockholm six months earlier to meet with Bruce Hopper (a Harvard political science professor working for OSS), then travelled to Switzerland in September 1943. In Berne – just a few weeks after Mendelssohn’s first Stockholm mission – Langbehn discussed peace proposals with future CIA chief Allen Dulles and his fellow OSS officer Gero von Gaevernitz, an economist of German-Jewish origin. It’s not clear just how much Himmler knew about these peace feelers, and to what extent he would have been prepared to act against Hitler if necessary to secure a separate peace with the Western Allies – or indeed to what extent Himmler and Hitler were working together all along to pursue these peace feelers: this remains one of the unsolved mysteries of the Second World War, and is likely to be explained more fully when David Irving published the second volume of his long-awaited biography of Himmler.

Allegedly, unfortunately for Langbehn, an Allied telegram identifying him in relation to the trip to Switzerland was intercepted by the Gestapo: whether or not Himmler had earlier approved of the mission, he now had to dissociate himself. Langbehn was arrested and executed in October 1944.

The grim fates of Hansen and Langbehn have long been known to historians, though there remains a good deal of mystery about the Langbehn-Himmler story. But until today nothing has been written about Robi Mendelssohn, who survived all of these treason arrests and trials entirely unscathed.

What is especially interesting is that at the end of October 1946 Mendelssohn arrived in London and told a version of the Hansen and Langbehn stories to MI5. Mendelssohn already knew, for example, that Langbehn’s arrest was due to the interception of an Allied telegram. The half-Jewish banker clearly still had high-level Berlin contacts, at least until mid-1944.

Most likely, after the failure of the July bomb plot, Mendelssohn decided to retire to his country home and keep out of politics. As a result he was never troubled personally by the Gestapo, even though his wife (who had her own range of contacts in Berlin artistic circles) was briefly detained during investigations of the July bomb plot conspiracy.

In 1943 he had paid the SS to secure his mother’s emigration to Sweden: she returned to Germany in 1946 and died in 1957 aged 90. The only casualty of the National Socialist era in Mendelssohn’s immediate family was an aunt who committed suicide in 1942, when she heard that she faced arrest.

An October 1946 entry in the diary of Guy Liddell, deputy director-general of MI5, reveals that it was Robi Mendelssohn who pushed for Abs to be given a key postwar role in the German economy. Robi, wrote Liddell, “has certain constructive proposals to make. He thinks it is hopeless to expect agreement with the Russians to run the whole of Germany as an economic unit. The only thing to do is to accept the ‘iron curtain’ and try and put the West on to a sound economic footing – to do this it is necessary to consult with experts in all the various fields, i.e. banking, industry, agriculture, etc..

“Robi could interrogate suitable people and they could, if necessary, be got over here. He thinks that if this is not done, and advantage is not taken of the swing to the Right in the recent elections, Germany will gradually sink into communism and starvation. He talked to Ned Reid [Sir Edward Reid, a member of the Baring banking family who was MI5’s main expert on City matters] about this, who agreed with his views and put him into touch with Playfair, the financial expert in the office of the Control Commission in London. [This was the future Sir Edward Playfair, a Treasury civil servant who later became head of the Ministry of Defence.] He told Playfair about his proposals and mentioned the kind of people he had in mind: one was a man called Abs, who was in the Reichsbank.

“Playfair took the view that it would be impossible to use a man who had served throughout the war in an institution which had been supporting the Nazi regime. Robi said that if this attitude was maintained, it would be really impossible to do anything. It was clearly no good digging out some old financier who had been out of the swim for the last fifteen years. He suggested that I should see Playfair and try and get some sense into him.”

It seems that at Mendelssohn’s instigation, the British (and more reluctantly the Americans) did indeed ‘come to their senses’. The Americans (in a hangover from the Morgenthau Plan) had wanted the separate German regions (Länder) to have separate currencies: indeed until July 1947 the US occupation policy was governed by a Joint Chiefs of Staff directive that forbade their authorities “to take any steps to strengthen [the] German financial structure”.

In contrast Abs (with British backing) successfully proposed that there should be a common German currency – the Deutsche Mark, introduced in the three western zones of Germany (British, American and French) on 20th June 1948. Soviet opposition to this new currency led to the Berlin Blockade from June 1948 to May 1949, which had to be countered by an airlift of supplies after the Western allies insisted the new currency should be used in West Berlin.

The introduction of the Deutsche Mark was one of the ways in which Hermann Abs shaped the postwar world, along the lines suggested by Robi Mendelssohn to British intelligence: what could be termed an anti-Morgenthau Plan. Instead of permanently weakening the German economy, the Western allies should take steps to build up the Federal Republic. Hermann Abs’s other major contribution to this plan was his successful renegotiation of German debts (including both pre-war debts and reparations for the First and Second World Wars): the London Debt Agreement (Londoner Schuldenabkommen) was signed in February 1953, with Abs leading the German side. Not coincidentally, at almost exactly the same time the West German Bundestag ratified an agreement for long-term German payments to the new Israeli state.

Within Germany, Abs became the leading official in the Credit Institute for Reconstruction (Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau), established in 1948 to distribute 20 billion marks in ‘Marshall Aid’ for German reconstruction, though it was not until November 1949 that he was permitted to travel to the USA for the first time since the war.

Abs then became the key man in protracted negotiations during the 1950s for the return of German assets frozen in the USA. In a separate chapter, I shall analyse this process and some of the individuals and interests involved. (By the end of the 1950s Abs was working closely with former Nuremberg prosecutor Sir Hartley Shawcross, later Lord Shawcross, representing major financial interests in Britain, Germany and elsewhere in drawing up new international agreements for the protection of overseas investments.)

In summary, it appears that a tacit agreement was reached in the late 1940s – an agreement that held until roughly 1990. German political and business leaders would agree (in general terms) that they and their nation were ‘guilty’ of whatever their enemies wanted to allege. They would act as the military frontline of the Cold War, and to some extent finance it, while giving up any notion of an independent German foreign and defence policy. And they would hand over huge amounts of money, goods and technology to the new state of Israel.

In return Germany’s enemies agreed that a line would be drawn after the first phase of Nuremberg trials. There would be no endless witch-hunt against those who had held political or economic influence during the Third Reich, and Morgenthau-style plans for the complete crushing of the German nation would be shelved. While the German Reich would still be fractured into East and West, and remains fractured to this day even after the so-called ‘reunification’ thirty years ago, a substantial part of Germany would be allowed to become something resembling a ‘normal’ country. No constitution, no real sovereignty, no independent diplomatic or military role – but for pragmatists such as Hermann Abs and Konrad Adenauer, the Federal Republic was at least some semblance of ‘normality’, a far cry from the utter devastation promised in various ways by the plans of Henry Morgenthau, Earnest Hooton and Theodore Kaufman.

What Abs didn’t realise when achieving this partial post-war settlement was that by 1990 the deal would have expired. With the end of the Cold War and the slow passing of the wartime generations, Germany’s enemies (in fact Europe’s enemies) chose to restart the witch-hunts. Instead of a general acknowledgment of German ‘guilt’, followed by a drawing of the line and ‘moving on’, there began a worldwide obsession with the ultimate crime – the ‘Holocaust’ – and a search for surviving individuals to place again in the literal dock of war crimes trials or the metaphorical dock of history. And acknowledgment of this ultimate crime was no longer a step towards rebuilding Germany and Europe (as Abs and Adenauer had intended), but a justification for flooding the White world with immigrants from every other race on Earth.

We can be sure that Abs and Adenauer had not foreseen this deluge: had others?

British documents unreported until today show that Robi Mendelssohn – the very man who had been a partner in the largest Jewish family bank supposedly seized by Hermann Abs on behalf of Deutsche Bank – was the man who persuaded the British to rescue this ‘nazi banker’ and secured his position postwar.

Time and again, historians have picked over the bones of the Abs story; but each time they have ignored Robi Mendelssohn. Moreover the same historians who are usually so keen to discover stories of wartime spies and Jewish heroism have completely ignored the fact that a half-Jewish banker – part of Germany’s most famous Jewish banking family – was an Allied spy inside the Third Reich.

Robi Mendelssohn died in the ‘artists’ colony’ town of Worpswede, Lower Saxony, in July 1996, aged 94. A few years earlier he had secured the return of a good deal of Mendelssohn family capital after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of ‘West’ and ‘East’ Germany. At exactly this time, his near contemporary Hermann Abs was facing a chorus of denunciation, banned from entering the USA as a ‘nazi’ and ‘war criminal’.

The successor and protégé of Hermann Abs as chairman of Deutsche Bank – Alfred Herrhausen – was the victim of what is still one of Europe’s most mysterious murders on 30th November 1989, three weeks after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Herrhausen – who like Abs was a close friend and colleague of Sir Frank Renouf – was killed by a car bomb near his home. The assassination was claimed to be the work of the far-left Red Army Faction, successors to the Baader-Meinhof gang, and the same terrorist unit was later blamed for the murder of industrialist Detlev Karsten Rohwedder, head of the ‘Treuhand’ organisation that was in charge of integrating the economy of communist East Germany into the Western system.

Rohwedder was killed by a sniper at his home on 1st April 1991. He had uncovered corruption on a vast scale within the East German apparatus, and many analysts allege that the Rohwedder and Herrhausen assassinations were carried out by ‘deep state’ elements in the Federal Republic who had benefited from corrupt East-West deals. During 2020 these allegations were supported by the four-part documentary series A Perfect Crime, broadcast on Netflix. The killing of Abs’s protégé Herrhausen was pivotal to the plot of a fictional drama broadcast worldwide in 2020, Deutschland 89.

Almost a quarter-century after his death there remain only two brief and obscure British documents referring to Mendelssohn’s contacts with Allied intelligence. Given that he was reporting from such a high level in the Third Reich – and given his own antecedents – what did Mendelssohn tell the Allies about the events now known as the ‘Holocaust’? Given that they had such a high-level Jewish source, why are contemporaneous British documents so silent about the ‘gas chambers’ and associated matters?

On 27th August 1943, responding sceptically to early Polish reports about homicidal gas chambers, the head of Britain’s Joint Intelligence Committee, Victor Cavendish-Bentinck, succeeded in having all reference to such supposed execution chambers removed from the text of an Allied declaration about German ‘war crimes’, insisting:

“I feel certain that we are making a mistake in publicly giving credence to this gas chambers story.”

This was more than a month after MI6 had made contact with Robi Mendelssohn in Stockholm and received his first report from the heart of the Third Reich. Mendelssohn’s recruitment was handled at the highest level of London’s intelligence bureaucracy and would certainly have come to Cavendish-Bentinck’s notice by the time of his ‘gas chamber’ scepticism. Did Mendelssohn ever provide any intelligence to change his mind, or anything at all about what we now call ‘the Holocaust’?

In October 2020, the Mendelssohn story formed part of a dossier about Hermann Abs, including other contradictory statements and actions from influential Jews – a dossier that would have formed part of the defence case for Lady Michèle Renouf, former wife of Abs’s old friend Sir Frank Renouf, had Dresden prosecutors gone ahead with their long-planned case against her for ‘Holocaust denial’.

Now the Mendelssohn story is part of a forthcoming book by Peter Rushton, research consultant to the Renouf defence team.

With writers, lawyers, filmmakers, and many others – including Germans in their 80s and 90s such as Horst Mahler and Ursula Haverbeck – being locked up for months and years at a time for ‘holocaust denial’, surely the time for secrecy is long gone.

During the Cold War there might have been good reasons why the Western Allies never revealed the story of their German-Jewish spy Robi Mendelssohn – especially as this related to sensitive histories of German peace proposals and the role of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who like Robi Mendelssohn had mysterious ties to British and American intelligence, before disappearing in January 1945 – a case that has never been solved.

British and German authorities are now under an obligation to be fully candid about their archives on Robi Mendelssohn and German Jewry: official half-truths and evasions are unacceptable while historical sceptics are locked up for asking awkward questions.

4 thoughts on “The banker, the model and the Jewish spy – inside a Dresden courtroom drama”

Comments are closed.