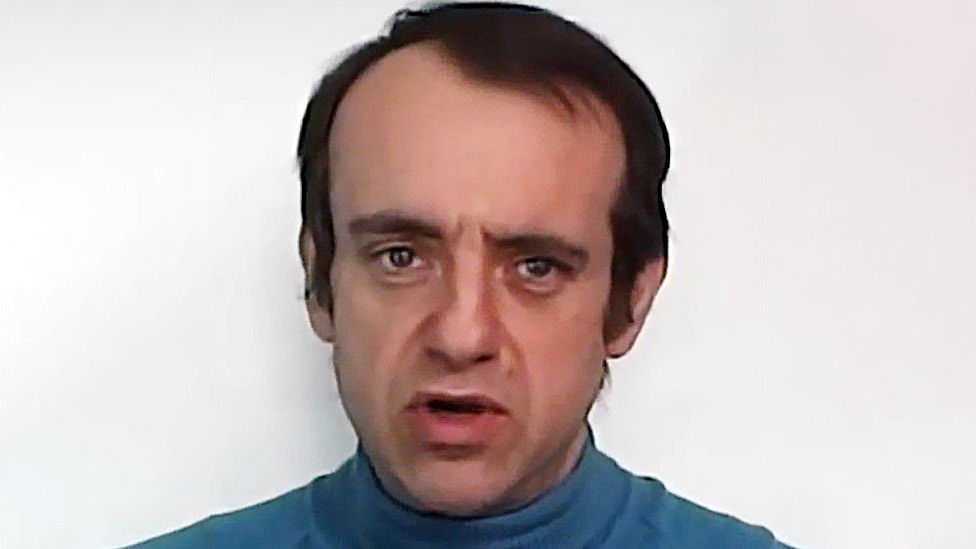

This interview was given by Vincent Reynouard from his Edinburgh prison on 23rd November to the French weekly Rivarol.

It was published in Rivarol’s 7th December edition and in French on Vincent’s own blog. Any errors in this English translation are our responsibility.

Rivarol:

On November 10, you were apprehended by the police in the small house where you had been living in hiding, in the middle of the Scottish countryside. Since then, you have been incarcerated in Edinburgh prison. How are you?

Vincent Reynouard:

Before answering your question, I would like to point out that my arrest is a striking rebuttal of two kinds of argument one often hears:

1. Our adversaries present the revisionists as a handful of fanatics who would deny historical realities that are supposedly obvious or proven a thousand times over;

2. Within the nationalist right, many argue that the revisionist fight is useless (or even considered counterproductive), on the grounds that the general public are interested above all in the future, not the past.

If these arguments were valid, then a Vincent Reynouard would not interest anyone, except his own feeble gang of followers. The authorities and his adversaries would therefore leave him to “rant and rave” in his corner. However, I was apprehended because in June 2021, France issued an arrest warrant against me. The justification for this warrant being: I have to serve a one-year prison sentence for a revisionist video posted on YouTube in early 2014! My channel has since been shut down and the video has disappeared from major internet sharing platforms. I would add that on November 10th, the Scottish public prosecutor opposed my bail on the grounds that the British police had “employed significant means to locate [me]”. So I was arrested for a 30-minute video, completely forgotten or unknown, that was released nine years ago! Who now will be made to believe that revisionism doesn’t matter?

Rivarol:

It might be argued that your arrest is due to your activism, which has not wavered, quite the contrary.

Vincent Reynouard:

That doesn’t alter anything. My opponents took steps to have me kicked out from YouTube, Facebook, VK, Vimeo, etc. They had my blog and my site shoarnaque.org blocked in France. They closed my Patreon and Buymeacoffee account which was used to receive donations. They have prevented our customers from being able to pay for their order by credit card or PayPal. In short, they gagged us and almost asphyxiated us financially. Only a very limited public, made up of very convinced people, now follows me. In other words: I speak in the catacombs of the Internet in front of a very small assembly of those faithful to the revisionist cause. But it was still too much. I had to be apprehended to be silenced. My whisper—for it was no more than a whisper—was still too much for the keepers of Memory. What an admission!

Rivarol:

They might argue that even this small audience listening to you includes impressionable people, likely to be incited to “racist” acts. The judges who sentenced you heavily in 2015 invoked such grounds.

Vincent Reynouard:

I would answer with the facts: During thirty years of activism, how many violent acts have been attributed to me? None! At the end of August 2020, a stranger wrote on the entrance wall of the Oradour Memorial Centre: “À quand la vérité ? Reynouard a raison.” (“When will the truth be heard? Reynouard is right.”) This is the only known act – because it has been publicised – that can be attributed to my influence. However, that question – when will the truth be heard? – frightens them to the utmost, because even as a distant echo from the catacombs of the Internet, the truth terrifies apprehensive liars. This is why I repeat: my arrest is an admission by our adversaries, a blatant admission of the importance of revisionism.

Rivarol:

Returning to the topic of your imprisonment. Are you keeping your spirits up?

Vincent Reynouard:

I am in excellent spirits. It must be said that after the prisons of Forest (in Brussels), Caen, Valenciennes and Fleury-Mérogis, I am starting to get used to it. The prison world has its realities and its rules. If you rebel against them, then you will experience hell, a hell that you will have made for yourself. If, on the other hand, you accept these realities and follow these rules, then you will be fine. This is my personal experience. It conforms to the principle that your existence depends above all on yourself. Certainly, I do not dispute the importance of external elements; but ultimately your own mentality counts for more. There is a saying that “it’s not because an occurrence is grave that it makes you suffer; it’s because it makes you suffer that it seems grave to you”. Face that occurrence in a good spirit and it will lose much of its gravity. Prison is the ideal place to put this teaching into practice.

Rivarol:

Are you alone in your cell?

Vincent Reynouard:

No, precisely I share it with a 43-year-old Scotsman, arrested for cocaine trafficking, who is awaiting trial. We are not at all from the same world, but I accept him and, above all, I avoid taking a position of entrenched opposition. For example, Steve (that’s his name) watches TV from 7:30 a.m. to 11 p.m. However, he has the delicacy to set the volume quite low. In addition, he watches many “reality” type documentaries: the life of a team of researchers in Australia, of a family moving to Alaska, of fishermen on the high seas, of restorers of old vehicles found in barns or forests… Sometimes it’s interesting. I then interrupt my activities to watch with him. It’s my way of not taking a stance of entrenched opposition: I take an interest in whatever’s good on TV. The rest of the time, I focus on my own activities. I would add that Steve is very clean, not only in himself, but also in respect of the cell which he cleans every two days. Therefore, the cohabitation is going well. We pool our stuff so that no one is short of anything.

Rivarol:

What is your cell like?

Vincent Reynouard:

Similar to all the other cells I’ve known. 15 to 18 square meters, cream-coloured walls (with graffiti), a large window that can be partially opened for ventilation, a dozen shelves in three places, two bunk beds (the mattress is foam, of adequate thickness, covered with a sheet and duvet with cover), and a “bathroom” corner of about three square meters. Separated from the cell by a partition with a door, there’s the WC and a sink with hot and cold water. Privacy is guaranteed. While waiting to turn on my desk lamp, I write in a corner of the bathroom so as not to disturb my cellmate’s sleep.

Rivarol:

Do you talk with the guards?

Vincent Reynouard:

They are all very polite. Some are even friendly. They call us by our first names, which helps to establish a certain camaraderie. All do their best to respond to our requests and thus make our detention easier.

Rivarol:

Is your food good and sufficient?

Vincent Reynouard:

It’s very good. In the morning, an inmate brings breakfast to the cell. Each prisoner receives a bread roll of about 200 grams, 150 grams of cereal (crispy “Rice Krispies” or “Corn Flakes”), a portion of jam and half a litre of semi-skimmed milk. On Friday mornings, we receive a small paper bag filled with tea bags, sugar and powdered milk. That’s to last for the week. I would add that each cell is equipped with a kettle to prepare our hot drinks. Three menus are offered for lunch, three menus for the evening meal. They are chosen the day before, during our morning period outside the cell, with a guard who comes to the upstairs hall. I always choose menu #3, which is vegetarian, and dessert #2, fruit. The vegetarian menu often includes a large baked potato and a soup. I mix the two and I get a delicious meal. The only problem is that the portions are only just sufficient.

Rivarol:

How are the days spent?

Vincent Reynouard:

The schedule is as follows. 7:15 a.m.: Two guards pass through the cells for morning roll call; 7:45 a.m.: Breakfast; 9:00-10:00 a.m.: exit to the upstairs lobby; noon: meal; 2:00-3:00 p.m.: Lobby outing; 3:00-4:00 p.m.: walk in the courtyard; 4:30 p.m.: Evening meal; 7 p.m.: evening roll call by two guards. The two exits and the walk are not compulsory: if you wish you can stay in your cell. For my part, I go out in the morning and in the afternoon into the hall.

Rivarol:

What do you do there?

Vincent Reynouard:

You can do a variety of things. One can meet the other prisoners, either in the hall or in their cell, and chat over a cup of tea or coffee. For those who want a hot snack, four microwave ovens are available in the lobby. There are also six tables with chairs, either to read the newspaper, or to play dominoes, or to converse; a ping-pong table and a very nice pool table. On each floor, people can play: some are very good players. For my part, I take advantage of the period of free time to go to the library upstairs. It contains 300 books, almost all in English: biographies, stories and novels mainly. Some religious works (Christian and Muslim) and some sociology books. I go there to leaf through them, because none of them interest me enough to read them in full. Then I go to the showers. The shower room has four individual cabins. The door reveals your feet, torso and head. You can’t adjust the water temperature, but it’s just fine. Knowing that in the morning, the showers are not in frequent use, I stay there for about fifteen minutes. I take this opportunity to wash my underwear which I can then dry on the heating of the cell. This morning shower is a real luxury.

Rivarol:

Are there many coloureds in the prison?

Vincent Reynouard:

Not where I am, no. Of the 40 detainees (20 cells with two in each cell), there is one black and two Asians (one Vietnamese and one Burmese). I had noticed that Scotland was not a land of immigration. The prison seems to confirm this.

Rivarol:

Have you socialised with any of the prisoners?

Vincent Reynouard:

Yes, despite the language barrier, or more precisely the accent barrier. The Scots speak English with such an accent that to my ears it’s almost another language. However, I’ve socialised with a Bulgarian, a Romanian and a Pole, who are also subject to an extradition request.

Rivarol:

Do your fellow inmates know why you are in prison?

Vincent Reynouard:

Yes, because I have been featured in the British press, including The Sun which prisoners read every day. The news spread like wildfire. People came to see me, some out of sheer curiosity, others to ask me what I was writing about the Holocaust. I summarised revisionism for them. They listened attentively, without appearing either revolted or incredulous. I don’t pretend to have convinced them, but they are interested: I was asked for my latest book, because some knew – I don’t know how – that my book on Oradour was coming out soon. I promised to show it to them, if they allow me to receive a copy.

Rivarol:

Let’s talk about the future. Do you think you will be extradited to France?

Vincent Reynouard:

At first, I was sure of it. But my court-appointed lawyer pointed out that in Scottish law there is a strong argument in my favour: I have committed no offence here and in the UK, revisionism — for which France is seeking my extradition — is not considered to be a crime. Here you are allowed to challenge the supposed reality of the Holocaust. Therefore, and according to Scottish law, my extradition to France is by no means obligatory; it might even be illegal. This is why my court-appointed lawyer handed my case to another lawyer, who is a specialist in extradition matters. A preliminary hearing will be held on December 8 before the court concerned. The hearing that will settle my fate has been set for February 23, 2023.

Rivarol:

This is good news, but when it comes to revisionism, Robert Faurisson pointed out that there is ni foi ni loi ni droit (“neither trust, nor law, nor rights”). One can therefore imagine that despite the legal position, the Scottish authorities will nevertheless hand you over to France.

Vincent Reynouard:

Naturally, and I have always been mentally prepared for this. When I came out of prison in 2011, after serving a one-year sentence for revisionism, I did not cease my activism. With my videos, I even moved up a gear by addressing the younger generations. In 2013, my opponents brought a case against me for a revisionist video, and specifically charged me with seeking to recruit youth. In my view, this is no accident. These proceedings led to my conviction, in February 2015, to two years in prison. This was twice the maximum penalty provided by law. Of course, I knew that on appeal, this sentence would be reduced to one year, but I had understood that from now on, the French authorities would do everything to throw me in prison and keep me there as long as possible, knowing that I was unbreakable. Hence my flight to England, where Providence offered me a little house near London. Until 2021, I enjoyed relative peace: France convicted me (so far to 29 months in prison), but the British authorities remained inactive. I knew, however, that this respite was temporary. In October 2021, I narrowly escaped arrest. I then lost everything: my accommodation, my personal belongings and my private lessons. I only thought of saving my computer and my archives on Oradour, because I wanted to finish my new book which remains the work of my life (I am the only revisionist historian of Oradour). After a few adventures, I found a room in Scotland, which I rented under a false name. I had nothing then: I was an illegal immigrant with no social security or legal status. Anyway, I knew the next step would be arrest or death. So I hastened to finish my new book on Oradour. At the same time, I undertook to synthesize my work on the Holocaust. In my eyes, this was less important because on this subject, humanity has the authoritative works of Carlo Mattogno, Jürgen Graf, Germar Rudolf, Arthur Butz, Thomas Kues and Robert Faurisson. For my part, I am only a disseminator to the French-speaking world… I was arrested only a few days after making the final corrections to the book on Oradour. I see in it a message from Providence telling me: “Now that you have finished your life’s work, it is necessary to publicise it and to clarify the situation for posterity.” My being in jail – that’s great publicity for my book! That’s why I’m in no way despairing of the future. On the contrary, I have many plans, even if I have to remain in prison.

Rivarol:

What are these projects?

Vincent Reynouard:

For relaxation in prison, I solve maths problems that I set myself. This allows me to revise ideas and contemplate them in order to be able to explain them better to students: my experience has shown me that the more we delve into an idea, the more we master it and the more we can explain it clearly (in the words of Boileau). For example, I found a very simple and very visual demonstration of the Pythagorean theorem with a square and four right-angled triangles. I am also developing a method for learning fractions, difficult notions for many students, simply because we do not insist enough on the essential nature of a fraction. Finally, I’m dealing with integral calculus, in order to make it accessible to teenagers. I would like to present all this in a didactic manual for the pupils. If I stay in prison, I will find the time. I also got back to drawing. My goal is to improve my abilities so as eventually to create two revisionist comics! One on Oradour, the other on Auschwitz. This project would take me at least two years, time to learn how to create dynamic drawings and build scenarios.

Rivarol:

You have also mentioned writing your memoirs.

Vincent Reynouard:

Yes, and I have started. I have already written twenty pages. I want to tell how my life prepared me for revisionist militancy. My objective is therefore not – or not only – to set out the revisionist arguments that convinced me, but to explain how Providence prepared me to become a resolute revisionist fighter, always present in the front line. My memoirs will make it possible to understand why I have faith and trust in Providence, today more than ever.