Today I am able to reveal a ‘Most Secret’ decrypted telegram from 1941 which for the first time provides official evidence of connections between Savitri Devi – Greek-born national socialist author – and the intelligence services of the Axis powers. This revelation (at least in part) refutes the suggestion by French nationalist writer Christian Bouchet, that Savitri Devi had invented this aspect of her past in order to enhance her status among postwar ‘neo-nazis’.

Savitri Devi became world-famous among national socialists soon after her death in 1982, largely thanks to the German-Canadian publisher Ernst Zündel, who republished her books and issued tape recordings of interviews that he had conducted with her in Calcutta in 1978.

During her lifetime, she was a close comrade of many leading national socialists such as Colin Jordan in the UK and George Lincoln Rockwell in the USA, but until now there was relatively little contemporaneous archive material about her activities.

Savitri’s interviews with Zündel and her self-published postwar memoir, Defiance, gave some details about the circumstances of her marriage to the Brahmin journalist and activist A.S. Mukherji and their joint activities for the Axis cause, but until now no author or researcher had tracked down evidence from wartime documents. This absence of archival evidence enabled Christian Bouchet (a radical French nationalist and admirer of Julius Evola) to disparage Savitri’s autobiographical account. Bouchet’s critique appeared in 2004 alongside contributions by his Italian colleagues Vittorio de Cecco and Claudio Mutti, and selected writings by Savitri herself, in Savitri Devi Mukherji: Le National-Socialisme et la Tradition Indienne.

Born Maximiani Portas in Lyons, France, in 1905, Savitri Devi’s mother was English, while her father was a French citizen of half-Italian, half-Greek ancestry. As an adolescent she became a Greek nationalist, and the travails of Greece during and after the First World War led her to detest British and French foreign policy.

Her first visit to Athens at the end of 1923 produced a lifelong devotion to the ideals of Classical Greece, which she came to identify with the broader ideals of European civilisation and national socialism. Though she later thought in Aryan racial terms, in the mid-1920s she was committed to “Hellenism”, identified as “a civilisation of iron, rooted in truth; a civilisation with all the virtues of the Ancient World, none of its weaknesses, and all the technical achievements of the modern age without modern hypocrisy, pettiness and moral squalor.”

On 9th November 1923 – the historic day when Adolf Hitler’s national socialists (of whom the young Maximiani as yet knew nothing) – made their first bold bid for power on the streets of Munich, the future national socialist Maximiani/Savitri was visiting the Acropolis. Two months later she began her studies at the University of Lyons (where decades later the great revisionist scholar Professor Robert Faurisson taught). After an outstanding undergraduate career, she returned to Greece for postgraduate studies.

By the time she visited Palestine (then under the British Mandate) for the first time in the spring of 1929, she was already a convinced ‘anti-semite’ – or rather, as she would prefer to put it, anti-Jewish, but this visit deepened her dislike of Jews and Judaism – and broadened it into a fundamental rejection of Christianity in favour of pantheistic nature worship.

By the end of 1931, possibly as a result of reading the theories of the great German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann (most famous for his excavation of Troy) concerning the Indian origins of the Aryans, Maximiani Portas had begun to take a close interest in India, and a legacy following her father’s death allowed her to visit India for the first time in 1932.

Almost immediately she began to regard India not only as the original home of the Aryans, but as her own spiritual home – and it became her literal home for most of the rest of her life. After four years of travel and study around many remote areas of the country, she settled in Calcutta at the end of 1936. A year later she began working for Calcutta’s Hindu Mission as a travelling lecturer – openly declaring to the Mission’s president Srimat Swami Satyananda, that she was a European pagan and a devotee of Adolf Hitler’s national socialism. In fact Satyananda himself was also an admirer of Hitler’s Germany.

There is of course a paradox here, in that Adolf Hitler was an admirer of the British Empire’s rule in India, while Savitri Devi was working with its Hindu opponents. Moreover, most Hindu anti-imperial activists were in those days associated with the political left (or merely forged alliances wherever they could), though there were a small number of genuine Hindu supporters of national socialism such as the brothers Ganesh and Vinayak Savarkar. And in the 2020s Hindu nationalism has become a very different project, with the rise to power of the reactionary BJP and Prime Minister Narendra Modi, whose clique of tycoons are natural allies of Israel.

Savitri Devi was looking beyond quotidian politics, to an Aryan ideal that had been lost in her ancestral Greece but was being advanced in Germany and whose roots (she hoped) could be revived in India. Later explanation of her motives links this Hindu missionary activity to her hopes for the rebirth of a pagan Europe:

‘‘If those of Indo-European race regard the conquest of pagan Europe by Christianity as a decadence, then the whole of Hindu India can be likened to a last fortress of very ancient ideals, of very old and beautiful religious and metaphysical conceptions, which have already passed away in Europe. Hinduism is thus the last flourishing and fecund branch on an immense tree which has been cut down and mutilated for two thousand years.’’

At the start of 1938 she was introduced to the journalist A.K. Mukherji, a history graduate of London University from an old Brahmin family. He similarly combined Hindu nationalism with admiration for Hitler and national socialism.

During 1935-37, Mukherji had produced a fortnightly magazine – The New Mercury – in cooperation with the German consulate in Calcutta. This was closed down by the British authorities, after which Mukherji began publishing another journal, The Eastern Economist, backed by the Japanese consulate.

During 1939 Savitri had been considering returning to Europe to work for national socialism, but was torn between wishing to forge closer ties to Germany, and wishing to continue her work to rediscover the Indian roots of the Aryans. The decision was made for her during 1939, when the British Empire’s declaration of war against Germany made it impossible for her to travel. Though their intense friendship was political and spiritual rather than romantic, Savitri and Mukherji married on 9th June 1940. This gave her a British passport, with which she again made plans to travel to Europe, this time on an Italian ship – but the very day after her marriage, Italy joined the war. The ship was stranded in Italy for the duration – and so was Savitri.

During the early years of the war (by her own account) Savitri Devi and her husband Mukherji carried out espionage missions on behalf of Germany and Japan (both before and after Japan entered the war in December 1941). They regularly obtained intelligence from Allied officers whom they invited for drinks parties every Wednesday evening at their home in Calcutta, then passed their reports via four Indian couriers who regularly crossed the border into Burma to meet with Japanese intelligence officers.

Savitri further claimed that her husband had links to Subhas Chandra Bose, the militant Hindu nationalist who led a rebel ‘Indian National Army’ fighting on the Japanese side. Her biographer Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke (most famous for his doctoral thesis on The Occult Roots of Nazism), based his chapter about these wartime activities entirely on Savitri’s own memoirs, and was therefore criticised by Bouchet as a “pseudo-historian”. However, it should be admitted that no relevant archival records from the British intelligence services were available to Goodrick-Clarke (who died in 2012).

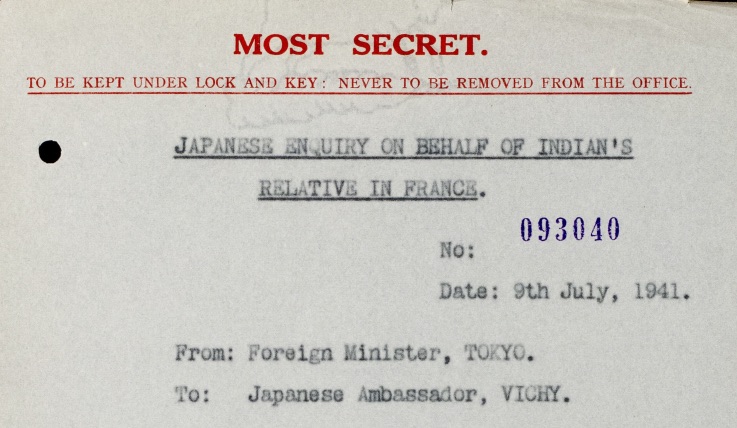

What can now be confirmed for certain is that Savitri Devi’s husband Mukherji was a valued asset of Japanese intelligence. On 9th July 1941 the Japanese Foreign Minister, Yosuke Matsuoka, sent a secret coded telegram to his Ambassador to France, Sotomatsu Kato, based in Vichy. Mukherji had asked the Japanese Foreign Office to make enquiries on Savitri’s behalf about the welfare of her mother, Julia Portas (who was born an Englishwoman but decades earlier had acquired French nationality after her marriage).

Foreign Minister Matsuoka emphasised that Mukherji had “a special connection with the Japanese Consulate-General in Calcutta”. Though it is only one document, this form of words, and the fact that the welfare of his wife’s family was being prioritised by the Japanese, is strong confirmatory evidence for Savitri Devi’s account of her and her husband’s wartime work for the Japanese cause.

What the Japanese didn’t know was that their codes were being broken by British and American cryptographers, even when (at the stage of the war) Japan was still neutral. Then and now, the partnership between Anglo-American codebreakers was central to what became known as the “special relationship”, and Japanese codes were the only serious aspect of the intelligence war where the Americans had made more progress than the British.

The decrypted telegram referring to Savitri Devi appears in the files of the British codebreaking agency GC&CS (then based at Bletchley Park). Matsuoka used the diplomatic cypher known in the West as the “Purple Code”, which by summer 1941 the British had only recently begun to read.

It was the Americans who were the first to crack the “Purple Code” in September 1940, having built their own version of the relevant Japanese encryption machine, which the Americans codenamed MAGIC. In early 1941 (though still officially neutral in the war) they gave their British allies two MAGIC machines, which were installed in Singapore and Bletchley Park.

Unlike the so-called ‘ULTRA’ secret (the British cracking of the German ENIGMA code), news soon leaked that the Japanese codes had been broken. Thanks to intelligence from the German diplomat Hans Thomsen, based at the German embassy in Washington, the German foreign ministry knew in April 1941 about American success against the Purple code. They passed this information to their Japanese ally, but the Japanese failed to act on it and continued using the Purple code throughout the war, thus compromising not only their own security but also that of their Axis partners.

Until the British security service MI5 or its Scotland Yard partner Special Branch release their files on Savitri Devi, this one intercepted telegram remains our clearest evidence of her connections to the world of secret intelligence. We do know that the Special Branch file exists and was catalogued as RF 404-46-51, and it can be assumed that an MI5 personal file was created by 1962 at the latest.

Thanks to the Savitri Devi Archive maintained by Greg Johnson, we can read the details of her prosecution by the British military occupation authorities in Germany, where she served four months of a three-year prison sentence imposed in April 1949 for distributing illegal propaganda, and was then given a five-year expulsion order.

Despite this order, Savitri Devi managed to obtain a new Greek passport in her original name Maximiani Portas, and returned to Germany in 1953 where she began to extend her connections with loyal national socialists including the great fighter pilot, Hans-Ulrich Rudel. Via fellow veterans based in Madrid, Rudel had business and political links to a community of German expatriates including scientists who later worked for the Egyptian government of Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Fragmentary evidence in official files (combined with my personal knowledge of some of the individuals involved) suggests that by the 1960s, Savitri Devi was connected to important liaison work involving the Egyptians and European national socialists. This is a subject on which I shall carry out further research as new documents become available in the British archives.

Nasser’s Egyptian government was secular nationalist, so there would have been no difficult issues involving Islam for the Hindu nationalist Savitri in this period. Moreover, one of the Third Reich’s most important experts on the Jewish question – Propaganda Ministry official Johannes von Leers – was working for the Egyptian government on similar tasks during the 1960s, including responsibility for anti-Zionist radio broadcasts produced in Cairo.

Von Leers was a crucial link between Savitri Devi and the academic elite of the Third Reich, including Heinrich Himmler’s Ahnenerbe.

In the autumn of 1960 (again via Rudel’s connections to the national socialist diaspora) Savitri visited Madrid for the first time, where she met prominent figures such as Otto Skorzeny and Leon Degrelle. Taking up residence in France (where she worked as a teacher) from early 1961, Savitri now turned her attention to her mother’s native country – England. She had a good (though non-political) friend living in London, Muriel Gantry, whom she had known since the 1940s, and at whose home she died in 1982.

At exactly the point in 1961 when Savitri began to build stronger contacts in England, an openly national socialist wing of the British racial nationalist movement was growing. Savitri visited a British National Party camp held on the estate of Norfolk landowner Andrew Fountaine. Fellow overseas guests at this camp included the German national socialist Bruno Ludtke (a Hitler Youth veteran who had served in the Wehrmacht as an 18 year old during the last year of the war), and Robert Lyons, from the National States’ Rights Party in the USA.

These international links contributed to a split within the BNP, and in February 1962 Colin Jordan, John Tyndall and their national socialist wing of the party were ousted: they formed a new organisation – the National Socialist Movement. It was this NSM that (as I discussed in an earlier article on this blog) hosted the more famous 1962 camp near the Gloucestershire village of Temple Guiting in August 1962, leading to the Cotswold Agreement and formation of a World Union of National Socialists.

George Lincoln Rockwell, founder of the ‘American Nazi Party’, was smuggled into the UK, evading official bans, and attended this camp, co-founding WUNS with Jordan. Savitri Devi met Rockwell for the first time at the Cotswold camp, and became a great intellectual and spiritual influence on his political development. The inaugural issue of Rockwell’s magazine National Socialist World, published in 1966 and edited by Dr William Pierce (who later founded the National Alliance) included an 80-page abridged version of Savitri Devi’s The Lightning and the Sun.

Eventually Savitri’s ashes were taken to the USA where they are interred at the headquarters of New Order, the organisation founded by Rockwell’s successor Matt Koehl and now led by my H&D colleague Martin Kerr.

During the months leading up to the creation of WUNS, MI5 files on Jordan show that he and his deputy John Tyndall had met with the Egyptian military attaché Saad el-Shazly during 1961 and 1962 and had discussed Egyptian funding for anti-Jewish activities in Europe, including cooperation between European national socialists and the Egyptian intelligence service.

As I have explained elsewhere, it was this rather than any electoral ‘threat’ that prompted Israeli agents in the UK to step up their activities against the NSM.

MI5 records also show that the French heiress Françoise Dior, briefly married to Jordan, was a close friend of Savitri Devi. Though evidence is presently sparse, it seems possible that Savitri (who we now know to have had experience of some sort of intelligence work on behalf of the Axis more than twenty years earlier) would have involved herself with covert projects of this kind, whether moving funds around Europe, semi-legal publishing and propaganda work, or intelligence collaboration with the Egyptians.

I hope and expect that further information will be discovered soon as further areas of British security and intelligence archives are opened to scholarly research.

Note: The document quoted above, which I discovered in the UK National Archives at Kew, is catalogued as HW 12/266. It is not available online, but can be viewed by researchers at the Archives.