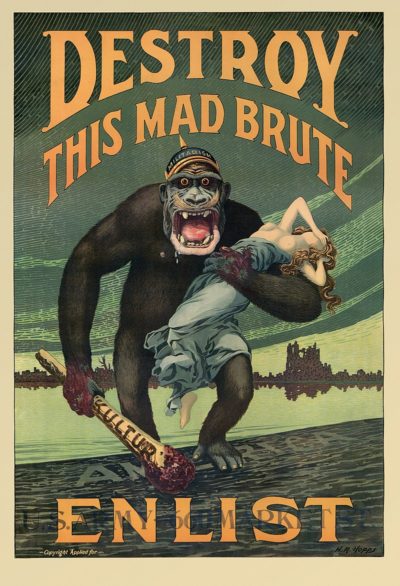

The brutality of Allied terror bombing of Germany – though given spurious justifications then and since – was partly rooted in demonisation of German culture and even the German race.

This virulent hatred of Germany – not only of Adolf Hitler and National Socialism but of Germany itself – can be traced as early as the First World War.

Anti-German propaganda of that era is now renounced by all ‘right-thinking’ liberals, and atrocity propaganda during that war has long since been accepted as grotesque fiction (unlike atrocity propaganda from the Second World War era, which has become unchallengeable historical orthodoxy, protected by criminal sanctions against revisionists – seen as 21st century heretics in most European countries).

Naturally, much propaganda was promoted in wartime by official government agencies – but some of the most extreme anti-German hatred during the First World War came from Joséphin Péladan, a well-known French Catholic author who revived Rosicrucianism.

In Péladan’s 1916 book L’Allemagne devant L’humanité et Le Devoir des Civilisés (‘Germany before Humanity and the Duty of Civilised Peoples’), he set out “to expose how the Germanic race had become inhuman, that is, opposed to the universal principles and conditions of the progress of the species”.

For Péladan, Germany was now “the incarnation of evil” and for the past century France had been bewitched and “poisoned” by German philosophy and culture. Péladan singled out the composer Richard Wagner and the philosopher Immanuel Kant among those who had turned France into a “spiritual and moral colony of Germany”.

The enemy was not simply on the battlefield but in German culture itself, which had to be extirpated: “German thought is in the Sorbonne”.

Péladan’s proposed solution was to expel all Germans back to German territory, and then cut them off from all trade and other interactions with the rest of the world.

In 1888 Péladan had been co-founder of the Kabbalistic Order of the Rose-Cross, the earliest French occult society. This society organised classes on what it termed “Christian Kabbalah”, seeking mystical insights in the Hebrew Bible. Péladan later broke away to form another “Mystic Order of the Rose + Croix”, with himself as “Grand Master”.

For years Péladan called himself Sâr Mérodack, a reference to the Babylonian god Marduck. His occult activities might seem absurd to a 21st century reader, but during my recent analysis of conspiracies against Adolf Hitler, including the 1944 ‘bomb plot’, I discovered that several of the key conspirators within German military intelligence (the Abwehr) were bonded by loyalties to esoteric movements.

Some of these were conservative opponents of national socialism. Walther Wiebe, head of the Stettin branch of the Abwehr, and his deputy Count von Knyphausen were both members of an Ariosophist order, the Bund der Guoten (‘League of the Good’).

This ‘League’ was a semi-religious, semi-political cult founded by Kurt Paehlke, who promoted the notion of a ‘United States of Europe’. His followers Wiebe and Knyphausen were (during 1943-44) the key lieutenants of the main Abwehr conspirator, Colonel Hansen, controlling a trio of special agents whose task was to build contacts with British and American intelligence agencies.

For more on the background to these esoteric conspirators and who ultimately controlled them, click here to read my essay on the plots to assassinate Adolf Hitler.

Tsarist Russia also used extreme religious imagery in its anti-German propaganda, with frequent descriptions of the Kaiser as Antichrist or Satan. In one of the earliest war propaganda films – Uzhasy Reimsa (‘The Horrors of Reims’) – Russian filmmaker Grigorii Libken depicted a German officer attempting to rape a nurse on the altar of the cathedral. A priest holding a cross intervenes, but then German shells destroy the cathedral. In Russia such propaganda was rooted in the political/national role of the Orthodox Church, with the Russian nation seen as being fundamentally at war with Germany since the days of the medieval Teutonic Knights. Stalin later revived similar concepts (despite Communism being in theory atheistic) annexing Orthodoxy and Russian patriotic themes and even calling his war against Germany “The Great Patriotic War” (a title still used in Russia today). Perhaps the most famous propaganda picking up that theme was in two films by Sergei Eisenstein with music by Prokofiev – Alexander Nevsky (1938) and Part 1 of Ivan the Terrible (1944).

Extreme anti-German sentiment among British religious leaders was rare, but a prime example was the Bishop of London, Arthur Winnington-Ingram, whose views were privately described even by Britain’s Prime Minister at the start of the war, H.H. Asquith, as “jingoism of the shallowest kind”.

In one of his sermons during 1915, Bishop Winnington-Ingram preached:

“Everyone that loves freedom and honour … are banded in a great crusade – we cannot deny it – to kill Germans; to kill them, not for the sake of killing, but to save the world; to kill the good as well as the bad, to kill the young as well as the old, to kill those who have shown kindness to our wounded as well as those fiends who crucified the Canadian sergeant, who superintended the Armenian massacres, who sank the Lusitania, and who turned the machine-guns on the civilians of Aarschott and Louvain – and to kill them lest the civilisation of the world itself be killed.”

Note the Bishop’s uncritical repetition of an atrocity story about German troops supposedly having crucified a Canadian sergeant with bayonets. This was rumoured to have happened near the Ypres battlefield in April 1915 and was widely repeated in propaganda, but no evidence was ever produced and it is now assumed to have been a myth. Nevertheless, a bronze sculpture of this alleged crucifixion was made by a British artist in 1918. It was later withdrawn from exhibition after this atrocity propaganda was discredited, but the sculpture was controversially re-exhibited at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec, in 2000.

At the very start of the war, German forces were accused of atrocities in Louvain (Belgium) and the Daily Mail (one of the most virulently anti-German British newspapers at that time), used the headline “Holocaust of Louvain” on 31st August 1914.

One important difference between the First and Second World Wars is that despite cynically manipulating anti-German sentiment as part of his campaign to win the 1918 General Election within weeks of the Armistice, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and his senior ministers swiftly abandoned this stance.

In fact during the 1920s leading British statesmen sought to restrain their French counterparts’ continuing Germanophobia. Speaking to the Imperial Conference at Downing Street in June 1921 (a gathering of leaders from the UK, the Dominions and the Indian Raj), Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon emphasised that it was not in Britain’s interest to crush her former enemy, and that London’s policy was “the re-establishment of Germany as a stable State in Europe. She is necessary, with her great population, with her natural resources, with her prodigious strength of character, which we realised, even when we suffered from it during the war; and any idea of obliterating Germany from the comity of nations or treating her as an outcast is not only ridiculous but is insane. The policy we have set ourselves to has been to give her a chance of economic recovery – not entirely from a selfish point of view, but because in her recovery is bound up the industrial future of ourselves as well as of other nations.”

Curzon added that the above approach meant Britain was at odds with French politicians, who were in the main “strongly aggressive chauvinists… [who] make it difficult for any Minister, and undoubtedly render our task of pacification in Europe, particularly with Germany, exceedingly difficult.”

Likewise in July 1925, London’s most senior General, Lord Cavan, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, told the Empire’s chief strategists at a meeting of the Committee of Imperial Defence that “it was essential to the future security of Europe that Germany should take her place alongside the Western Powers. The Eastern boundary of civilised Europe was now the Russian frontier and it would be disastrous if Germany were driven to find a new orientation towards the East.”

During the 1930s there was constant tension in British policymaking between views such as those expressed above during the 1920s, and a rival Germanophobe approach typified by Sir Robert Vansittart, head of the Diplomatic Service from 1930 to 1938. Vansittart found himself opposed to successive Prime Ministers Stanley Baldwin and (especially) Neville Chamberlain: he often ‘leaked’ information to their rivals, Anthony Eden and Winston Churchill, even when the latter were backbench opponents of the government Vansittart supposedly served.

For most of British history, Germany (and the various German states that existed prior to unification in 1871) had been seen as an actual or potential ally of Britain against its European rivals, notably France and eventually Russia. That began to change during the first decade of the 20th century: Vansittart viewed this change not as a temporary phenomenon but as recognition that any strong united Germany was (so he claimed) a fundamental threat to British interests.

Unlike most of his colleagues, Vansittart continued this Germanophobe obsession during the early Cold War (by which time he was in retirement but regularly contributing to House of Lords debates). For example both Vansittart and the Second World War propagandist Sefton Delmer were leading campaigners against Adenauer’s West Germany being allowed to rearm during the 1950s.

One consequence of this anti-German (not simply anti-Hitler) hatred was the decision to break up German territory among several different states after 1945.

Anti-German policies of this kind – which took their most extreme genocidal form in the notorious ‘Morgenthau Plan’ of 1944 – can be traced in the private papers of leading politicians. For example, Hugh Dalton – Churchill’s Minister for Economic Warfare, in charge of the ‘dirty tricks’ side of the war effort as ministerial chief of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) – recorded in his diary on 15th January 1941 a lunch with Polish exile leader General Sikorski, accompanied by Józef Retinger, a leading Freemason and descendant of Polish-Jewish converts to Catholicism, who became one of the architects of postwar European federalism. The senior civil servant at Dalton’s ministry – Gladwyn Jebb, a young disciple of Vansittart – was also present.

Jebb explained to this influential Anglo-Polish gathering his theory regarding how Germany had to be handled:

“so long as all Germans, just because they speak German, are put together in one state, they will, just by reason of their numbers and capacities, be a menace to everybody else. This would be equally true whether their state was nazi, communist, or democratic, monarchist or republican. The real peril to the peace of Europe is the conception of Deutschtum. Therefore, there should be no ‘Germany’ after the war, but a number of German states, reasonably content to be separate.”

This discussion took place five months before the Soviet Union entered the war and eleven months before the USA entered the war, but even at this point – January 1941 – Germany’s enemies within the Allied elite were already planning her postwar fate. Note Jebb’s use of the word Deutschtum – German identity itself was defined as the enemy, not simply National Socialism.

There were still other, dissenting voices within London’s elite. For example Guy Liddell, a senior officer in the British security service MI5, wrote in his diary in November 1944:

“The subordination of various aspects of the conduct of the war to the American elections is becoming more and more irritating. …Morgenthau’s suggestion that Germany should have her machinery removed and be turned into an agricultural country is presumably a manoeuvre to obtain the Jewish vote. Declarations on the subject of the future of Palestine also operate in this sense.”

Perhaps the most trenchant and well-informed British critic of the Germanophobe policy that had come to dominate his country’s thinking under Vansittart and Churchill was the 20th century’s most eminent civil servant Lord Hankey, formerly Sir Maurice Hankey.

His views are all the more relevant because Hankey had been main architect of the British Empire’s bureaucratic machine during the First World War. Yet soon after the end of the Second World War, Hankey concluded that Unconditional Surrender and War Crimes Trials were:

“complementary parts of a policy of threats which was adopted in 1943, and has exercised the most sinister and far reaching influence ever since.”

It was in 1943 that the Allies began their policy of denouncing Germany for ‘crimes against humanity’, including what we now call the ‘Holocaust’ – although as I have explained elsewhere, and will detail further in a forthcoming book, the chairman of Britain’s Joint Intelligence Committee, Victor Cavendish-Bentinck and his deputy had already become the first successful ‘Holocaust revisionists’ – disbelieving the ‘gas chamber’ fables and ensuring that they were not at first endorsed by British spokesmen.

However, regarding the broader policy of “threats” against Germany, Lord Hankey continued:

“It embittered the war, rendered inevitable a fight to the finish, banged the door to any possibility of either side offering terms or opening up negotiations, … and made inevitable the Normandy landing and the subsequent terribly exhausting and destructive advance through North France, Belgium, Luxemburg, Holland and Germany. The lengthening of the war enabled Stalin to occupy the whole of eastern Europe, to ring down the iron curtain… By disposing of all the more competent administrators in Germany and Japan this policy rendered treaty-making impossible after the war and retarded recovery and reconstruction, not only in Germany and Japan, but everywhere else. … Unfortunately also, these policies, so contrary to the spirit of the Sermon on the Mount, did nothing to strengthen the moral position of the Allies.”

One need not share Hankey’s Christian faith to perceive the cogency of his argument.

Irrational Germanophobia helped create the post-1945 world – a disaster for Europe, as the great French poet Louis-Ferdinand Céline observed:

“The core of it all was Stalingrad. There you can say it was finished and well finished, the white civilization.“

So it appeared to Céline, who died in 1961. Perhaps in 2023 – after almost 80 years of the harshest winter for Europeans – we can see the first signs of spring: the end of the post-1945 settlement, the end of Germanophobia, and the renaissance of the True Europe.

If so, a truthful account of Europe’s 20th century history will have to be at the core of that renaissance.

4 thoughts on “Dehumanising the “enemy” – the roots of Germanophobia”

Comments are closed.